On the 23rd of October 1940 Adolf Hitler and General Francisco Franco, the leader of Fascist Spain, met at a railway station in the town of Hendaye in the Pyrenees region, right next to the border between Spain and Vichy France. At issue was whether Franco would enter the Second World War on the side of Nazi Germany. The meeting ended in a stalemate. Franco made extensive demands, including a desire to acquire large parts of French Morocco and Algeria. Hitler for his part later afterwards claimed to have detested Franco. However, the famous meeting at Hendaye was significant in so far as Franco did not commit one way or the other to the war. He left open the possibility of joining the Axis and Spain for the time being remained officially ‘non-belligerent’ rather than ‘neutral’. What this meant is that Franco would favour the Germans over the British, but he was not actively involving Spain in the war just yet.

The meeting at Hendaye is well known, but what is altogether more obscure is the planning which it set off in London. Winston Churchill and his government now feared that Spain would enter the war on the Axis side before too long. When it did an invasion of Britain’s small enclave at the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula, Gibraltar, would surely soon follow, and the British would be unable to fend off a land assault by the Spanish and Germans. This would have grave consequences for the British, who needed Gibraltar in order to ensure access to the Mediterranean for the Royal Navy to supply their beleaguered outposts on the island of Malta and in Egypt. Moreover, greater urgency was leant to these efforts from the autumn of 1940 when the British learned that the Germans had their own tactical plan in place for the occupation of Gibraltar. Under the conditions of Operation Felix Field Marshall Walter von Reichenau would oversee a German occupation of Gibraltar with Franco’s consent. Accordingly, in late 1940 plans were initiated in London to come up with a tactical response to the loss of Gibraltar in the event that Franco did bring Spain into the war on Germany’s side.

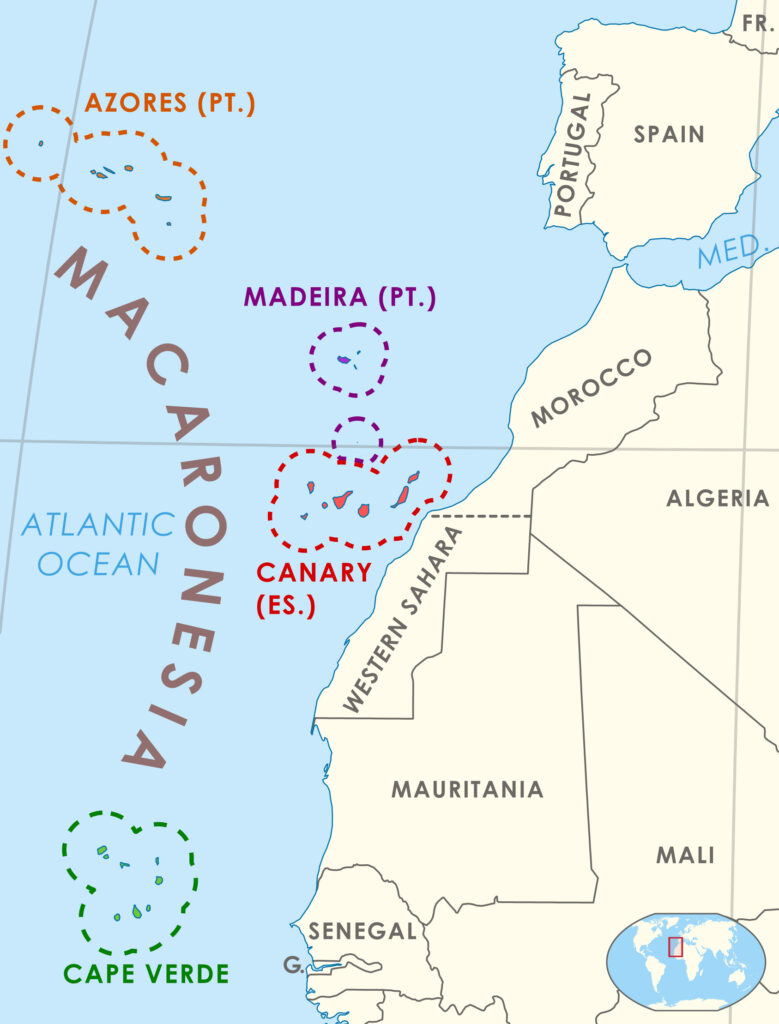

A number of plans were quickly being considered. These all focused on obtaining another naval base in close proximity to the Straits of Gibraltar, one which would not have a land connection to Spain and which the far superior Royal Navy could maintain control of. A range of island archipelagos in the mid-Atlantic were under consideration, notably the occupation of either the Azores Islands, Madeira island, or the Cape Verde Islands, all of which were Portuguese possessions. Portugal was Britain’s oldest ally, but these plans were being countenanced in the event that Spain and Germany also invaded Portugal. However, plans soon began to focus more exclusively on the Canary Islands, the chain of Spanish island colonies off the coat of north-west Africa. These were not only one of the closest sets of island chains to the Straits of Gibraltar, but their occupation would be striking directly at Franco’s Spain in the event that the Caudillo allied with Hitler.

The contingency plans for the invasion and occupation of the Canary Islands were codenamed Operation Pilgrim in the spring of 1941 and were outlined in a document produced by the Joint Planning Staff entitled ‘Capture of the Canary Islands’. The objective of the operation would, the document outlined, be to ‘capture and hold, for our own use, the island of Gran Canaria with the Harbor of La Luz and aerodrome at Gando’. The operation would be led by the Canadian commander Major General Victor Wentworth Odlum who would lead a small fleet of one battleship, four carriers, three cruisers and 27 destroyers against the Canary Islands. In total Odlum was to have control of about 24,000 men, which would be supported by the Royal Air Force. A night raid would first secure the major port of Puerto de la Luz on the island of Gran Canaria, which raid would be aided by submarine reconnaissance in the days leading up to the operation itself. The two key strategic targets were then the Harbor of Puerto de la Luz and the airfield at Gando. These could then be used as bases to acquire greater control over the island chain in the days that would follow. The planning was microscopic and there were even further schemes drawn up to have dozens of parachute infantry land on the island of Tenerife in order to sabotage key targets there in the days following the capture of Gran Canaria. Thus, would Britain acquire a strategic base some 1,500 kilometers from the Straits of Gibraltar in the event that the Rock itself was lost to the Germans if Spain entered the war.

There is no doubt that the British had every intention of initiating Operation Pilgrim if they needed to. In the spring of 1941 Churchill stated in a government memo that “If we are forced from Gibraltar, we must take the Canaries immediately, allowing us to control the western entry to the Mediterranean.” But Operation Pilgrim was ultimately never initiated. This was not because of any doubts concerning its strategic viability, but simply because the diplomatic and military circumstances changed in the course of 1941 and 1942. In all likelihood if Nazi Germany had continued to meet with military successes beyond 1941 Franco would have eventually entered the war on Hitler’s side, in which case Gibraltar would have been overrun and Churchill would have initiated the invasion of the Canary Islands. But the German invasion of Russia in the summer of 1941 changed the course of the war. When the German advance stalled in the Russian winter of 1941 Franco cooled his approach towards the government in Berlin. Consequently in the course of 1942 Spain’s official status was changed from ‘non-belligerent’ to ‘neutral’, a clear indication that it was no longer considering actively joining the war on Germany’s side. As it did so the plans for Operation Pilgrim were effectively shelved as the threat to Gibraltar dissipated. However, for a time between the autumn of 1940 and late 1941 there was a very real possibility that the British could have undertaken a military invasion of the Canary Islands in response to increased Spanish involvement in the war. It is a seldom heard story, but a striking statement of how vital the British considered the entryway to the Mediterranean as it largely stood alone against the Axis powers in 1940 and 1941.