Operation Jubilee: August 19th, 1942

Sometimes victory can be rescued from the jaws of defeat. This is certainly a maxim which applies to the Dieppe Raid by the Western Allies against the German-occupied French town of Dieppe in mid-August 1942. Viewed from a purely statistical perspective the Dieppe Raid, or Operation Jubilee, as it was codenamed, was a complete failure for the Allies, but in the midst of a strategic defeat Britain, America, Canada and their other Allies gained vital strategic information about how to undertake an amphibious landing and invasion of French soil, information which proved vital in planning and successfully implementing the D-Day landings less than two years later. This is the story of the Dieppe Raid.

As soon as the British had withdrawn their troops from France, with the evacuation from Dunkirk in May 1940, the British high command had begun assessing options for how to launch a medium sized raid on French soil, one which would involve thousands of troops. The goal here was twofold. It would provide a morale boost to a country which had seen only defeat against Germany in the initial stages of the war and it would also act as a test run for how to launch a modern amphibious warfare campaign. Britain had not undertaken any assault of this kind using the most modern weapons of war and it was deemed necessary to undertake an attack to see what lessons could be learned from doing so.

The time for such an attack became particularly propitious from the summer of 1941 onwards as Germany gave up trying to bring Britain to its knees, and instead turned eastwards to invade the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. Additional German resources had also been diverted to North Africa and the Balkans to aid Hitler’s erstwhile Italian allies. Consequently, German resources which had been funneled into France were sent east to Poland or south towards the Mediterranean, making the possibility of a successful British raid on France more plausible. In his memoirs Winston Churchill was clear that one of the main goals of this would be to act as a trial-run or preparation for a larger invasion of Western Europe in the years ahead.

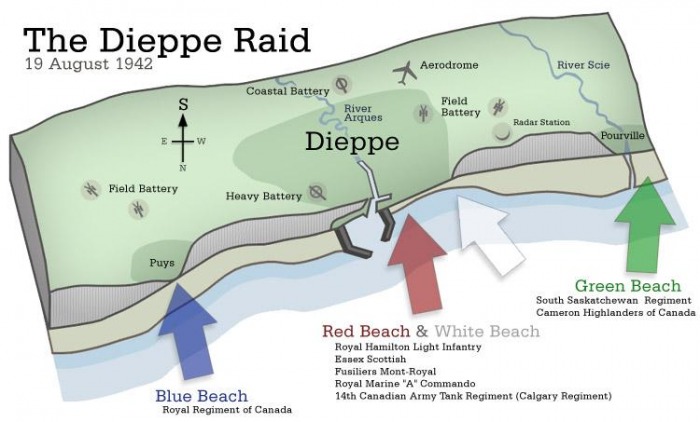

Eventually a plan was devised to capture the French port of Dieppe in the English Channel. A mid-sized fishing town on the Normandy coast, Dieppe was viewed as a good place for a raid as there are several beaches on the surrounding coastline. Operation Jubilee envisaged the landing of thousands of Allied troops who would capture the town. Local Nazi military targets would then be hit and any strategic advantages that could be gained at Dieppe would be taken before a withdrawal back across the Channel. General Bernard Montgomery, the head of the South-Eastern Command, was given operational control of the mission, though it would become a joint British-Canadian expedition, as the Canadian government was agitating to be given a prominent role in some significant piece of military action. As a result, the Canadian 2nd Division would be central to the Dieppe Raid.

Unfortunately, the plan which emerged in the weeks that followed was strikingly unimaginative. A frontal assault by the Canadians from the sea would be launched against the town of Dieppe, while British parachute divisions would land in and attempt to capture German batteries on the coastline on either side of the port. One of the key problems involved in the plan was that there was no provision made for an aerial bombardment of Dieppe and the surrounding region in the hours before the amphibious landing. Such an aerial bombardment would have knocked out key German batteries and gun-sites and created disarray before the main body of troops landed, but it was never thought to include this in the plans.

The raid was scheduled for the 4th of July 1942. Some 10,000 men were assigned to it, though in the end just over 6,000 of these would land on French soil. In addition the United States contributed 50 US Army Rangers and a small group of Free French fighters were also to be included, as well as some crack commando units. These would all depart from five separate British ports in the Channel, from Southampton to Newhaven. They would be supported by a huge flotilla of 237 ships, including eight British Destroyers, while air support would be provided by 74 squadrons of the Royal Air Force, having an average of about 20 planes in each squadron.

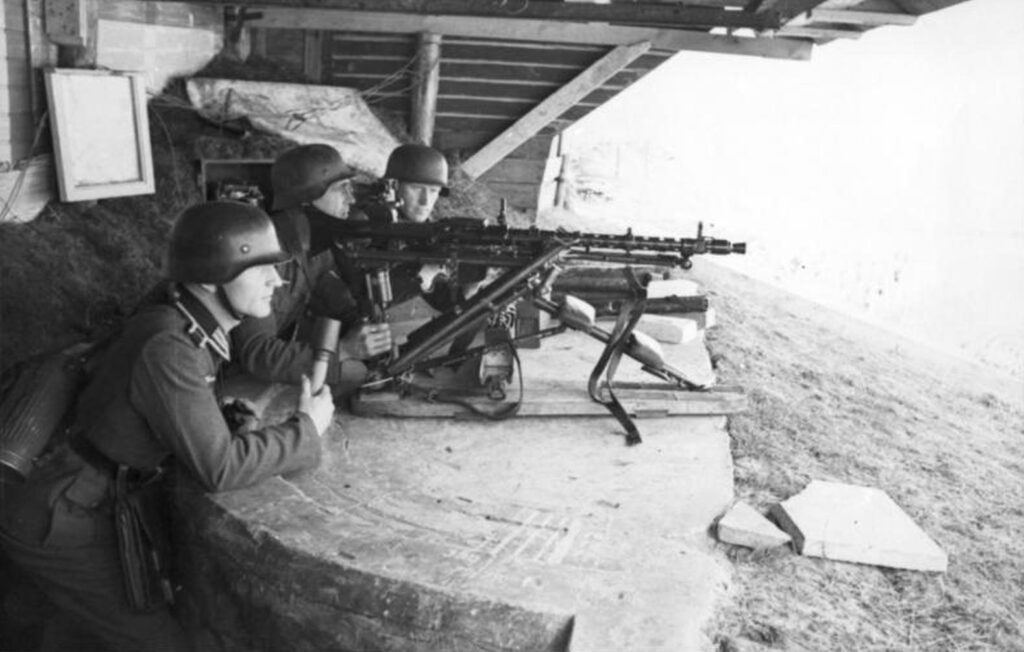

This initial plan changed considerably in the course of the early summer of 1942. Poor weather conditions ensured that the operation could not be undertaken in early July as had originally been intended. Then intelligence reached London that the Germans had received information about the preparations being made in the Channel ports of England and were strengthening their defenses around Dieppe. One key piece of knowledge that eluded the high command in London, however, was that the Germans had installed gun batteries into the headland cliffs around the port of Dieppe. Indeed there was poor intelligence gathering all round. Some of the pictures used for information on the beaches were taken from tourist photographs, rather than ones taken by Reconnaissance planes.

As a consequence of all this the raid on Dieppe was not finally launched until the 19th of August 1942. Operation Jubilee was initiated at roughly 4.00 am that morning with attacks on some of the German coastal batteries being undertaken by commando units. However, the landing of the main force in the ships had already been compromised with parts of the flotilla exchanging fire with German ships at 3.48am and as a result the Germans inland had advance notice of the attack.

In the hours that followed the main regiments began landing at a series of beaches along the coast which had been codenamed according to different colors such as Red Beach and Yellow Beach. These all generally met with heavy resistance and casualties quickly mounted. For instance, on Green Beach the landing was led by the South Saskatchewan Regiment’s 1st Battalion. They landed at 4.52am on the beach, but unbeknownst to them poor intelligence had led to them landing in the wrong spot. They became lost as they wandered inland and had to cross a bridge near the village of Pourville before they could reach their targets. This was a fatal misstep. By now they had been identified by the German garrison, which had set up machine guns trained on the bridge. As they attempted to make it over the Canadians and British bodies piled up and despite the heroics of a Lieutenant Colonel Charles Merritt, a commanding officer who ran across the bridge several times to prove it was possible to avoid German bullets while doing so, the advance was stopped. Eventually hundreds of men of that battalion were either killed or captured.

The developments amongst the Saskatchewan Battalion were mirrored elsewhere across the coastline around Dieppe as dawn broke on the morning of the 19th. To compound the matter the tanks which had been brought as part of the raid were ill equipped for a beach landing and became bogged down in the sand where they were soon easy targets for German anti-tank guns. Chaos reigned for hours thereafter, particularly once the German air-force, the Luftwaffe, sent planes into the skies around Dieppe. By 11.00am it was clear that an immediate withdrawal was necessary as all remaining units were under heavy fire up and down the French coastline. This took three hours and was eventually completed by 14.00pm. Consequently the entire Dieppe Raid or Operation Jubilee lasted only approximately ten hours. None of the strategic targets or goals was accomplished.