The experience of the First World War was in many ways more disturbing for an average soldier than that of even the Second World War. While the fighting at Stalingrad or Moscow in 1942 and 1943 was brutal, the sheer claustrophobia and psychological terror of the trench warfare which defined the First World War was its own type of hell. For the average soldier life for a few years in the mid-1910s consisted of living in a hole in the ground, constantly listening to artillery explosions and machine-gun rounds and occasionally being told by your commanding officer to climb out of the hole and actually run towards the machine-gun fire. As if this were not enough, one had to contend with a vast array of novel weapons such as mustard gas being used, which all sides agreed afterwards should not be allowed within the rules of warfare. Here we explore the particular experiences of the average German soldier during the First World War.

The experience of the First World War for German soldiers varied depending on where one was stationed. On the Western Front German, British, French and later American soldiers were confronted with the worst kind of industrial slaughter, living in trenches dug into the ground and occasionally running across a No Man’s Land filled with machine-gun fire, artillery explosions and mustard gas attacks. Conversely on the more expansive Eastern Front the campaigning often had the feel more of an eighteenth or nineteenth century conflict and as the Russian lines collapsed in the course of 1916 and early 1917 the German soldier stationed in Poland or further north-east can no doubt have felt himself to be infinitely more lucky than his contemporary in the trenches of north-western France. On the other hand perhaps the German soldiers on the Western Front might have felt more fortunate than the small but significant amount of German troops who were sent to fight on the Southern or Italian Front from 1915 onwards when Italy joined the war. Here the campaign devolved into trench warfare as well, but this was in the Alpine region of northern Italy and western Austria where, in addition to living in a trench and being shot at regularly, the average German soldier also had to deal with much colder Alpine temperatures and the occasional avalanche, whether natural or triggered by artillery fire. Others still found themselves fighting as allies of the Ottoman Turks in the Middle East or defending Germany’s colonial possessions in East Africa. Thus, the experience of the war for many German soldiers was determined by where they were deployed to.

According to label in accession file: “These German photographs purchased from a German officer by an American officer shortly after the Armistice.”

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the National WWI Museum and Memorial

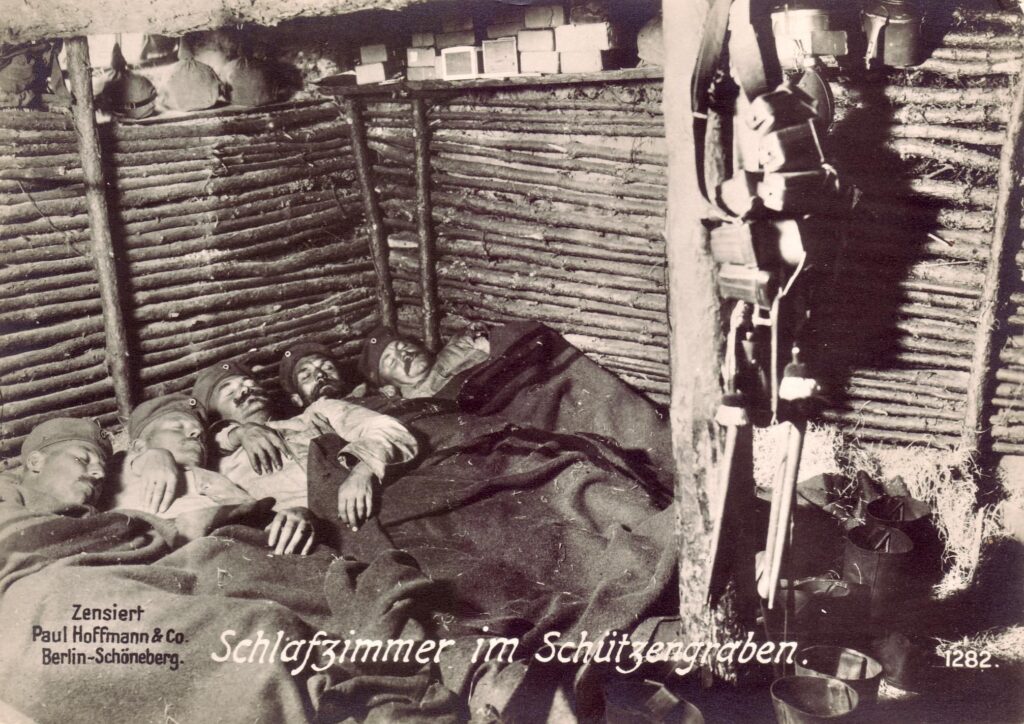

Yet, for most, when they were called up, they were headed to the Western Front, a large expanse of land which moved around occasionally but which was typically located in north-eastern France about midway between Paris and the Belgian border. This was a land of trenches between 1914 and 1918, long narrow ditches which had been dug into the ground for soldiers to reside away from the bullets which flew overhead across No Man’s Land in between enemy trenches. The average trench was about eight or nine foot deep, perhaps appearing to be more depending on the levels of sandbag defences on the ground above. Within these soldiers slept, played cards, had meals, went to the toilet and tried to do things like shave and brush their teeth, often using their helmets as basins. Basically life was lived down here in whatever fashion it could be. Other than death, boredom was the major enemy. More often than not units slept as well as they could during the day. Night, when it was dark, was the preferred time for repairing trenches, digging out new lines and even for launching attacks. Curiously, though, the greater danger to a German soldier in the trenches actually came from exploding artillery shells than the possibility of having to leave the trench and cross over No Man’s Land.

In fairness most soldiers did not spend extensive periods of time in the trenches on the front line. Units were generally sent forward to the front line trenches for periods of between one and two weeks, before being pulled back to either the support line or to wait in reserve. The support line effectively meant you were in the row of trenches which would become the front line in the case of a successful British and French attack, so in this instance you were living in a trench as well, albeit somewhat out of harm’s way. Soldiers who were in reserve were well back from the front lines and were often in camps rather than trenches, depending on where they were stationed and how great the troop build-up was there at a given time. Moving between these lines was arduous, as the average soldier carried a huge amount of equipment. The average soldier could expect to spend more time in the reserve lines than at the front lines, and there were also periods of rest and leave where soldiers were not anywhere near the front itself. For a German this might mean a stint in Belgium or Germany itself.

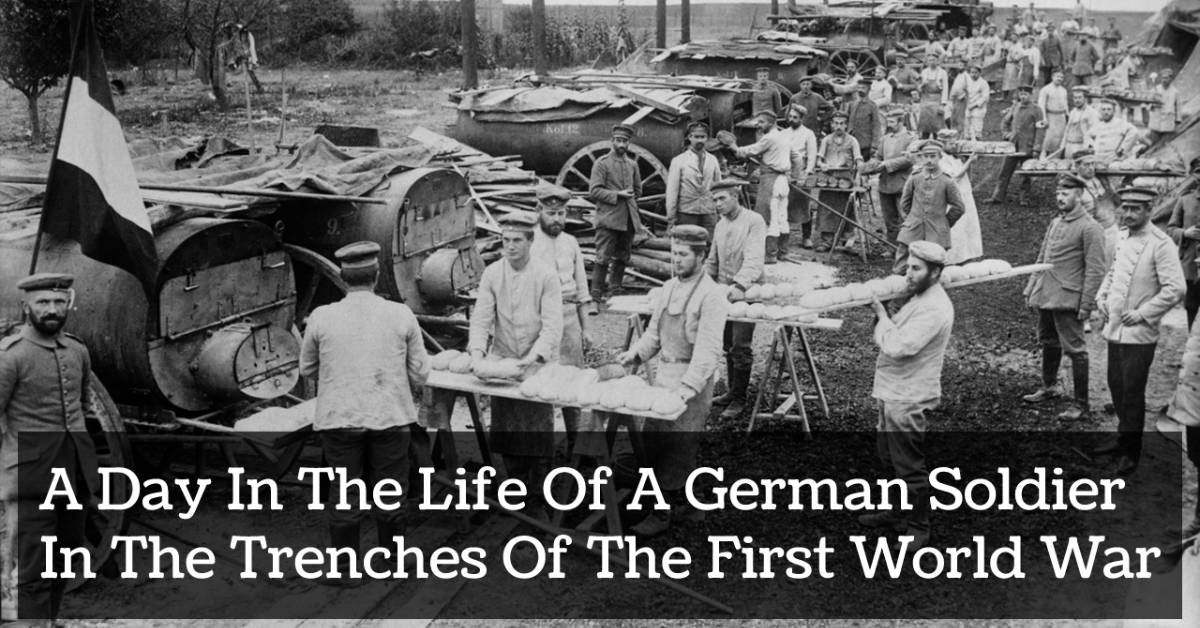

The diet of the average German soldier in north-west France was not good. Soldiers on all sides were critical of how they were fed, their rations often consisting of things such as bread and hard, dry biscuits augmented with cans of meat. By 1916 both sides were using alternatives such as ground dried turnips to make bread, as flour was in such short supply throughout Europe. But as bad as this situation was for the British and the French it was even worse for the Germans. Before the war broke out Germany was reliant on food imports to feed its population and with the Allied embargo imposed from 1914 onwards some basic food items became real luxuries in Germany and by extension the German trenches. Nevertheless, while the quality of the food was far from good there was rarely a suggestion of hunger and the dense carbohydrates received in dried biscuits and other staples meant the average soldier usually had an intake of well over 3,000 calories per day. And there was also booze. German soldiers enjoyed a more varied selection of liquor than the British and their beer and wine was often supplemented with a ration of schnapps. Tobacco was ubiquitous in an age when roughly two-thirds of adult males smoked.

As well as gunfire, artillery, mustard-gas, snipers and increasingly airplanes, the average German soldier also had to worry about bacteria. In fact this was more likely to kill him than a bullet. In the closed, confined, wet and muddy environment of the trenches diseases bred like wildfire. Rats were everywhere and so were fleas and lice. A simple cut from a rifle bayonet on a finger could develop into an infection and in an era where antibiotics were still not available (Fleming didn’t discover penicillin until 1928) these could eventually prove fatal. Common diseases such as influenza and typhus and other afflictions such as wounds turning gangrenous were rampant, but other things which were specific to the war also emerged, notably ‘trench fever’, a malaria-like disease which affected hundreds of thousands of troops, while ‘trench foot’ also afflicted tens of thousands. The latter was caused by boots and socks being constantly wet in the autumn and winter months. This was more than an inconvenience and could eventually lead to nerve damage or even require amputation as feet turned red and then blue. Finally, in the last months of the war the Spanish Flu, which killed more people than the fighting, ripped through the trenches of north-eastern France.

The life of the average German soldier in the trenches of north-east France was most famously articulated by Erich Maria Remarque in his 1928 novel All Quiet on the Western Front. Remarque was conscripted in the summer of 1917 at the age of 18 and assigned to the Western Front where he fought between Torhout and Houthulst. He only spent seven weeks in total there before he suffered a significant wound to his left leg from shell shrapnel and spent the rest of the war in hospital recuperating. It was a long enough stint though for him to be able to capture the extreme physical and mental stresses of fighting in the trenches for an average German during the First World War. Remarque later claimed it was a statement about a generation which was “destroyed by war, even though it might have escaped its shells.” The Nazis later banned the book in Germany believing it to be a criticism of German martial glory, but Remarque had the last laugh and an estimated 40 million copies of the book have been sold since.