The winter of 1944 saw Nazi Germany undertake its last offensive campaign of the Second World War. The Battle of the Bulge was undertaken in the heavily forested Ardennes region straddling Belgium and Luxembourg in December 1944. The goal here was to launch a surprise counter-attack against the advancing US 12th Army Group and the British 21st Army Group as they prepared on the borders here for a springtime offensive into the Rhineland region of western Germany. The Ardennes Offensive would involve German Army Group B consisting of the 7th and 15th Armies and the 5th and 6th Panzer Armies surging westwards in a fashion which resembled a bulge on maps days into the offensive and attempting to then circle back around and encircle the Allied forces. If they could be cut off and made to surrender, along with the Allied use of the port of Antwerp being interrupted, it was hoped that the Allies might decide to try to negotiate peace terms favorable to Germany. Alternatively, it might extend the duration of the war for long enough for the Western Allies to fall out with the Soviet Union.

The story of the Battle of the Bulge is well-known, but a more obscure aspect of it was Operation Greif, through which the German high command hoped to create chaos in the Allied ranks in the Ardennes region by spreading misinformation and if possible to secure a bridge over the River Meuse in the area. The Allies would attempt to destroy these bridges as soon as the Ardennes Offensive began, so it was important that one would be secured over the river which German armored units could then use to quickly traverse the river in the first hours and days of the campaign.

Operation Greif was to be headed by Otto Skorzeny, an Austrian born member of the Waffen-SS who had been heavily involved in several commando missions during the war, most notably the daring rescue of Benito Mussolini from a mountainside hotel in 1943 when he had been displaced as the leader of fascist Italy. Now Skorzeny was placed in charge of the new covert operation in the Ardennes region. The plan was relatively simple. Skorzeny would form a unit of special operatives to be known as Panzer Brigade 150. These men would wear American army uniforms and use captured American vehicles to disguise themselves as Allied troops. They would then secure a bridge over the River Meuse and begin undertaking other actions to create confusion amongst the Allied troops in the area.

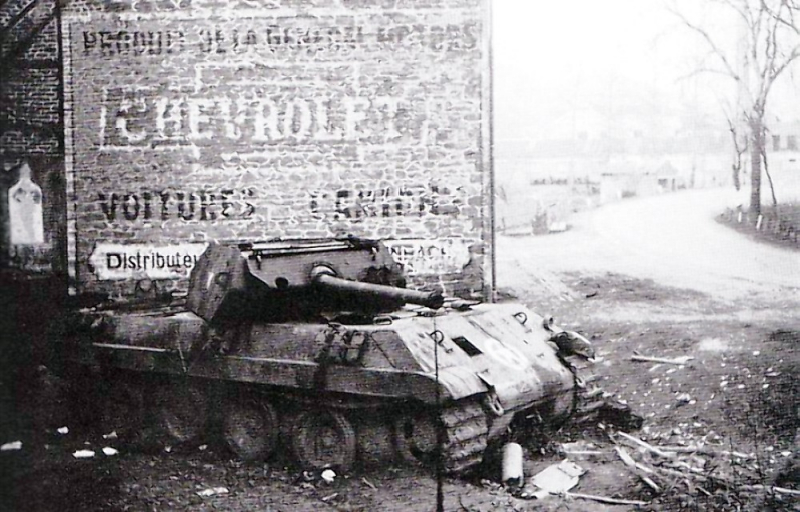

The Ardennes Offensive was to be launched on the 16th of December 1944, so when Skorzeny received his directive in late October he had only a few weeks in which to prepare. There were several obstacles to be overcome. He needed soldiers who could not just speak English, but do so in a passable American accent. It had originally been intended that he would identify well in excess of a thousand such men. Scores of American vehicles and tanks were also sought, but in the end Skorzeny could only put together a fairly rag-tag unit. Some of the men had barely passable English and the vehicles consisted largely of just trucks and jeeps. Only one American Sherman tank was located and in the end they resorted to disguising German Panzers as M10 Tank Destroyers. Consequently a very small force was eventually assembled. As a result, it would only be a motley crew of several dozen English-speaking commandos who headed behind enemy lines in the Ardennes region in early December 1944 as part of Operation Greif.

Despite the logistical and technical problems which bedeviled the operation, Operation Greif created chaos when it was launched on the 16th of December. Skorzeny’s men had orders to destroy fuel depots and ammunition dumps to inhibit the movements of the Allied forces in the Ardennes. They also moved road signs to send the Americans and the British in the wrong directions. If they encountered Allies units the commandos who had fluent English and passable accents would pass on bogus orders and misinformation sending entire units off in the wrong direction. They were also sabotaging telephone lines and radio stations to cut off communications between the Allies.

By the 17th of December it was clear that Panzer Brigade 150 would be unable to seize one of the bridges on the River Meuse. Accordingly Skorzeny, who was commanding the unit from behind German lines, requested that they be allowed to continue their sabotage efforts and try to attack targets in a more conventional sense from behind enemy lines, a request which was granted. Months later, when he was captured by the Allies, Skorzeny provided an account of much of this activity and described how his men sent entire Allied regiments in the wrong direction and convinced other units that they had been ordered to withdraw from villages in the Ardennes.

Within a few days it was clear to the Allies that there was a German brigade disguised as American troops operating behind their own lines. As a result American soldiers now took to stopping units they didn’t know and asking them questions which they believed only Americans would know the answers to. This resulted in serious disturbances itself, as some American troops were fired on in the belief they were the incognito German troops. There was a farcical element to it too though. The famous British general, Bernard Montgomery, had the tires of his jeep shot out by some over-zealous American GIs, while General Omar Bradley was briefly detained by an American soldier after answering Springfield at a US checkpoint when asked what the state capital of Illinois was. The soldier had the wrong answer to his own question and had believed Chicago was the Illinois’s state capital.

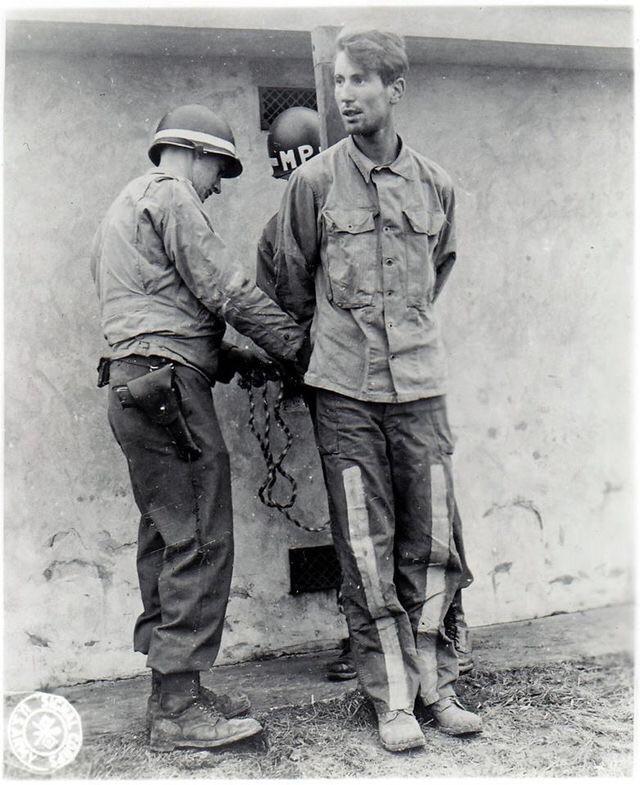

The confusion created was probably the greatest success of Operation Greif. By late December it was determined to withdraw the last of the disguised troops who had been sent behind enemy lines. Several had been captured by that time and were quickly tried and shot by Allied troops in late December and early January. By then the entire German counteroffensive was failing. While the Allies had initially been taken by surprise in mid-December, on the 26th of December General George Patton, by some estimates the most strategically gifted of the Allies’ generals, though a controversial figure, arrived with the US Third Army to relieve the German attack on the town of Bastogne. By early January the Allies were on the offensive again. Nevertheless, the Battle of the Bulge had been the sharpest action of the entire war on the Western Front. With 19,000 deaths and 70,000 more men wounded it was the single bloodiest battle fought by the American during the Second World War.