Operation Chastise (May 16th – 17th, 1943)

By 1943 it had become clear that Germany and its allies were almost certainly set to lose the Second World War in Europe, as the Russians continued to push the Wehrmacht back westwards and the Allies contemplated opening new fronts in the south and west of the continent. What was still at issue was how long it would take to obtain victory. Any and all means were under consideration as to how to shorten the war. Increasingly it was realized that one of the surest ways to bring the Axis powers to their knees was to strike at their economic power and their ability to produce war materiel. Nowhere was more critical to German industrial capacity than was the Ruhr Valley region in western Germany, so much so that it was here that France and Belgium occupied between 1923 and 1925 when the Weimar Republic had defaulted on its reparations payments from the First World War. It was an awareness of the economic power of the region that led to Operation Chastise in the early summer of 1943, a major effort to damage the German war economy.

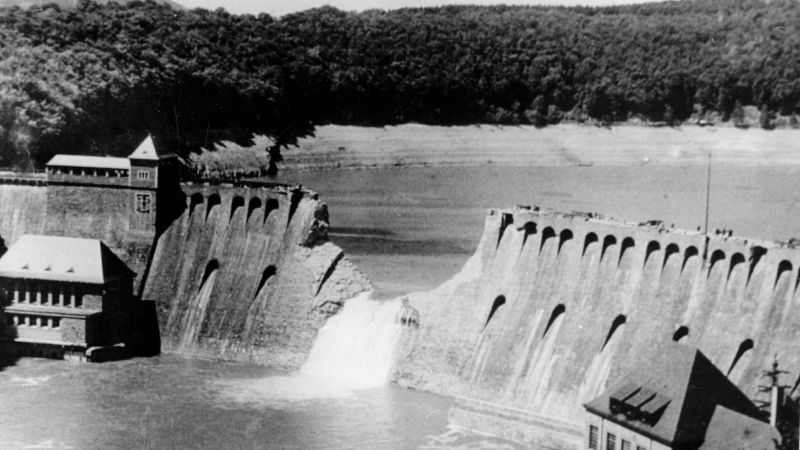

The plan which was developed in the course of 1942 and early 1943 was to destroy three major dams in the Ruhr Valley region, the Möhne, Edersee and Sorpe dams. These were critical to the economy and industrial output of the wider Ruhr region. For instance, the Möhne dam was not only responsible for regulating much of the water supply to this part of western Germany, but also generated large amounts of hydroelectricity which was in turn used to power the many factories in this part of the country, a substantial proportion of which were involved in producing war materiel, from tanks and armored cars to guns and airplane parts. If production here could be slowed down the war could be won faster.

Yet there was a problem. The Nazi high command was well aware of the strategic importance of these sites. Accordingly, key sites in the Ruhr Valley, including the Möhne, Edersee and Sorpe dams were heavily protected. In particular, each was surrounded by a network of anti-aircraft guns to prevent standard bombing raids from bringing down the dams, while torpedo nets had even been installed to stop torpedoes being launched against the dams from up or down river. As a result a wholly novel approach to attacking the dams was needed.

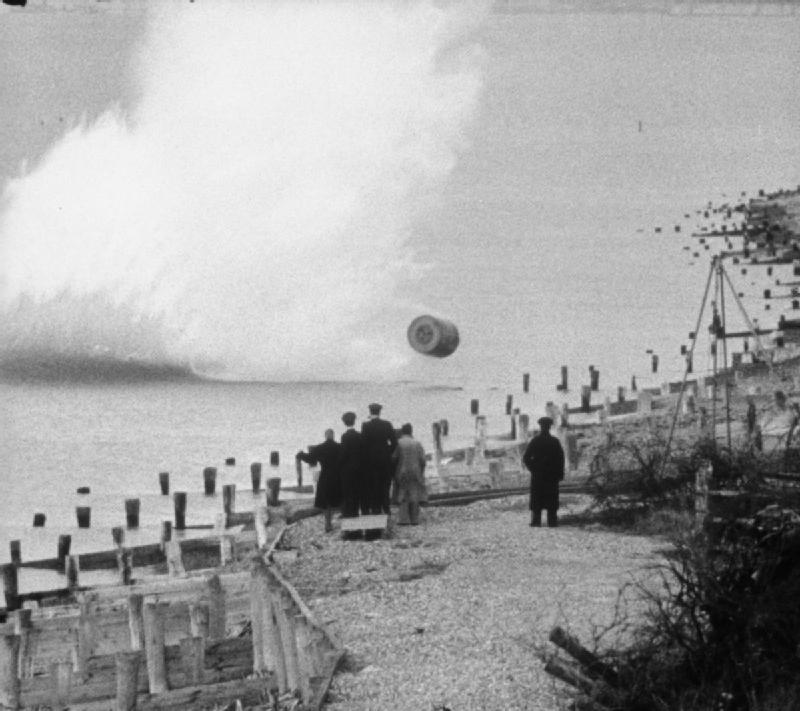

Into this space stepped Barnes Wallis, a British engineer who had been working on novel bomb methods and who had been lobbying in favor of a strategic bombing program to strike at German economic and industrial targets since the outbreak of the war in 1939. By 1942 Wallis was working on what has been called the ‘bouncing bomb’, one that could skip across water and consequently be dropped in a different location to where it was intended that it would explode. His experiments began with bouncing marbles in bathtubs of water early on in the war and had progressed by 1942 to manufacturing an actual 9,000 lb bomb in the shape of a cylinder. Originally Wallis had believed these could be used against German ships, but it soon became clear that they would be best suited to striking larger, static targets such as dams. As a result in the summer of 1942 tests were carried out in Wales to actually blow up a small disused dam. These were successful and plans for Operation Chastise were soon being advanced.

The operation was assigned to a new squadron which was put together especially for the task named 617 Squadron. ‘The Dambusters’, as those who took part in the mission have become known, were led by Wing Commander Guy Gibson, and consisted of pilots from Britain, the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. The plan was for 19 Lancaster Bombers to depart from Britain on the night of the 16th of May 1943 and deliver their ‘bouncing bombs’ in the early hours of the 17th over western Germany. These would be dropped upriver from the dams, with the intention that the ‘bouncing bombs’ would skip along the surface of the dammed water before exploding near the walls. The Möhne and the Sorpe dams were identified as the primary targets as these would inflict the maximum amount of damage to the Ruhr industrial area, while the Edersee was a secondary target.

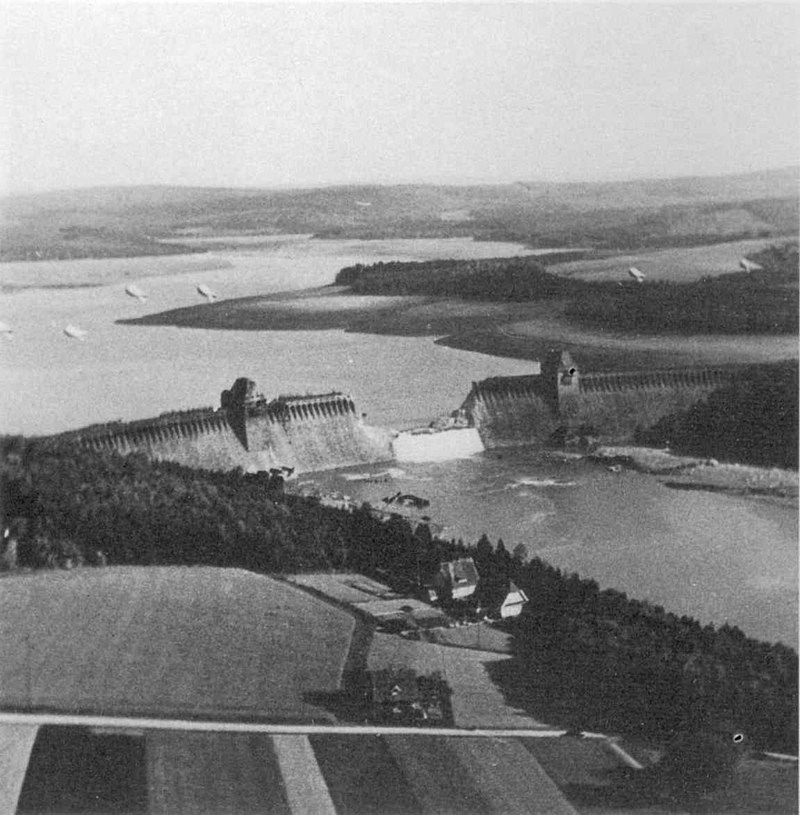

The planes of 617 Squadron took off from England from 21.28 onwards on the night of the 16th of May. They travelled along two routes, flying low once they were over enemy territory to avoid radar detection. Despite these precautionary measures several planes came under fire in the skies over the Low Countries and did not make it to Germany, either as a result of being shot down or having to turn back to England once damage was inflicted. The Möhne dam was the primary target and Gibson himself was the first to arrive here just before 00.30. After five attacks using the ‘bouncing bombs’ the dam here was finally breached, though with the loss of a plane which came under fire from flak anti-aircraft guns. Next up geographically was then Edersee dam which was also successfully breached, but the attack on the Sorpe dam was less successful. This was a huge earthen dam which was less vulnerable to a bomb attack and despite being hit multiple times by the ‘bouncing bombs’ was not breached. Aware of the futility of further attacks on it, the crews broke off to hit other targets in the region, including the Ennepe dam, before returning to England, during which journey several further bombers and crewmen were lost.

In total 8 of the 19 bombers which set out on Operation Chastise on the night of the 16th of May never made it back to England, while 53 of the total combined crew of 133 were killed, with three others who had crash landed being taken prisoner. Despite these losses, the overall mission was a resounding success. The Möhne and Edersee dams had been breached, flooding the Ruhr Valley region enormously. 330 million tones of water were released through the breach in the Möhne dam alone. Mines were flooded, houses were destroyed, factories were largely obliterated and roads, railways and bridges were wrecked in locations up to 80 kilometers away. The industrial capacity of the Ruhr region was drastically damaged for several months thereafter. Steel production, for instance, fell to less than 25% of what it had been prior to the attack, and coal production was severely reduced. Thus, although the dams were repaired in the months that followed and the German economy bounced back by the end of 1943 the actions of ‘the Dambusters’ during Operation Chastise severely dented the German war economy in the summer of 1943. As a result the Russian advance in the east accelerated in the second half of 1943 and Nazi preparations against the opening of a western front in France through the construction of the Atlantic Wall were also impeded. Therefore Operation Chastise played an important part in the course of the Second World War and the speed with which the Third Reich was defeated in its final years.