When looking back at the Second World War perhaps one of the most unusual aspects of the entire conflict is the speed and seeming ease with which Nazi Germany overran and conquered the Low Countries and France in just a six week period in the summer of 1940. After all the Allied forces of Britain and France had been so evenly matched against Germany in the First World War that the two opposing sides became bogged down in a stalemate in northeast France for four years. But in 1940 the same part of France was easily conquered by the Germans in just a few weeks. For years this rapid conquest of France has been attributed to the unpreparedness of the Allies and the nature of the German Blitzkrieg or Lightning War. But research in recent years has added a further explanation to how the swift conquest of France occurred. The German forces roaring westwards towards Paris and the Atlantic coast in the summer of 1940 were fueled by narcotics, in particular amphetamines.

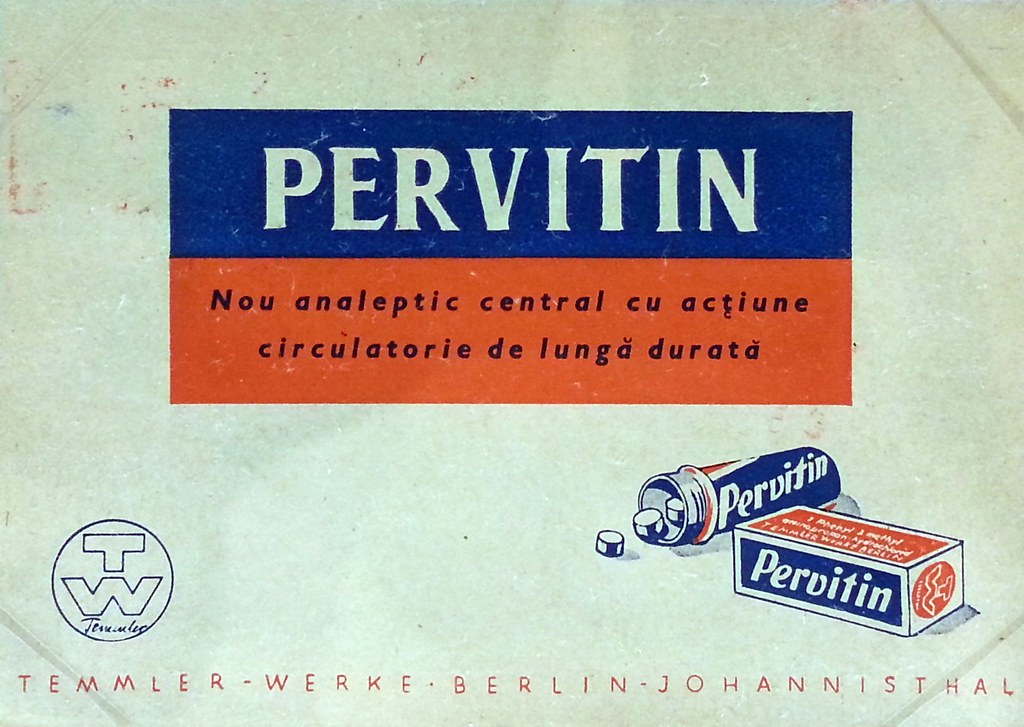

Amphetamine was first synthesized in Germany in 1887. It is a strong central nervous system stimulant which increases alertness, concentration and energy in moderate doses, and also allows individuals to go extensive periods, even days, without sleeping. Since the 1930s the German pharmaceutical company Temmler had begun marketing amphetamine under the name Pervitin. It may seem unusual to our times, in which amphetamines are generally classed as a highly controlled substance, but in the 1930s Pervitin was sold as a non-prescription drug throughout Germany. It could be freely bought by anyone who wanted it in a pharmacy.

Use of Pervitin by the German army quickly followed. Shortly after it became widely available on the market in 1938 it was brought to the attention of Otto Frederich Ranke, a military doctor and the director of the Institute for General and Defense Physiology, a department attached to the Wehrmacht. On the eve of the outbreak of the Second World War Ranke started undertaking trial studies of Pervitin amongst volunteers at his military lab in Berlin to test the applicability of the amphetamine as a possible battlefield drug. The results were promising and Pervitin, often supplemented with cocaine, was added to a list of drugs which were provided to rank and file soldiers in the Germany military.

Thus it was that when some three and a half million German soldiers and servicemen began preparing for the invasion of France in the late spring and early summer of 1940 many of them were allocated Pervitin tablets. This fueled the rapid advance through the Low Countries and northern France following the commencement of the campaign on the 10th of May 1940. We have instances of documentary evidence from many German soldiers at the time writing home to their families and describing how they were aided in their ability to stay awake and keep pressing forward by the Pervitin they were taking. In particular the tank brigades commanded by General Heinz Guderian were able to rapidly advance by simply not sleeping for days. Such was the ground they covered as a result that when reports reached Hitler and others back in Germany of where Guderian’s forces were in France by mid-to-late-May that often these same reports were believed to be inaccurate. The high command in Berlin assumed Guderian’s Panzer divisions simply could not have advanced as quickly as they did into France.

Nor was drug use in the Third Reich restricted to the rank and file of the Wehrmacht or to the use of Pervitin. Narcotics pervaded the upper echelons of the Nazi Party itself. Hermann Goring, the head of the Luftwaffe and Hitler’s designated successor for most of the war, was an opiate addict throughout the Nazis’ time in power. His specific addiction was largely to dihydrocodeine. Such was the extent of his addiction that when he was captured by the Allies in 1945 he was found to be in possession of a briefcase of thousands of pills and in the months that followed he had to be weaned off of his drug addiction in order to be fit enough to stand trial at Nuremburg in late 1945 and 1946.

But this drug use extended all the way to the top of the Third Reich. In the mid-1930s Hitler had employed the services of Dr Theodor Morell as his personal physician. The German chancellor suffered from many ailments throughout his life, including Irritable Bowel Syndrome, eczema, insomnia and an eye inflammation. Morell was an experimental doctor who treated these ailments with a variety of injections and pills ranging from vitamin cocktails to hard drugs. At first these were relatively moderate but over time Morell gradually began administering more and more drugs to Hitler. By the early 1940s these included a mix of everything from amphetamines and cocaine to barbiturates and opiates, while at night Morell would give Hitler a tranquilizer so he could sleep, having been heavily drugged with a variety of stimulants throughout the day.

This drug use increased as the course of the war shifted against Germany from 1941 onwards. By 1943 Morell was administering as much as 90 substances to Hitler every day, some of them relatively harmless, but many of them qualifying as hard drugs. It is now generally understood that in the final year or two of the Second World War Hitler must have been at least partially addicted to several hard drugs. Moreover, in his last days in Berlin in the spring of 1945 he would have been in serious withdrawal from these as Morell’s supply lines had dried up in the final weeks of the war.

The latter issue was symptomatic of the wider drug policy within the German armed forces as the war progressed. Where German soldiers had been provided with packs of Pervitin by the Wehrmacht when invading France in 1940, in later years the supply lines were damaged. Consequently there are instances of correspondence which have survived from the war in which German soldiers wrote home to their families and friends from the front, in which they requested that the recipients send some Pervitin with their next package, if they could find some at home. As such we see elements of addiction creeping in here, as well, undoubtedly, of just a desire to remain alert on the front as the situation for the average German soldier became more and more perilous from 1942 onwards. But ultimately no amount of Pervitin could change the course of the war by 1943 or 1944 in the manner in which it seems to have impacted on the Blitzkrieg of France in 1940. Yet, when assessing how the Nazis managed to be so successful in their military efforts in the initial stages of the Second World War, it is important to remember that some of their success was owing to the drug Pervitin.