The Development of Aerial Combat during the First World War – Part I

Just over a decade before the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 the first heavier-than-air powered aircraft was successful launched into the sky. This occurred at Kitty Hawk in North Carolina on the 17th of December 1903 when Orville and Wilbur Wright became the first individuals to pilot a modern aircraft. The plane had been developed from earlier experiments on gliders and was largely constructed of a flimsy aluminum shell. The brothers, taking turns to pilot the plane, managed four take offs that day, three lasting between 12 and 15 seconds, but the last becoming airborne for 59 seconds. Then the plane crashed and the Flyer, as they termed it, was damaged significantly. It was never flown again. From these rather tame beginnings air-flight would develop rapidly over the next thirty years, so much so that in 1927 Charles Lindbergh undertook the first nonstop flight from New York to Paris. No period was more critical in the development of air-flight than the First World War, as the major powers grasped the potential of planes to gain a strategic advantage and began developing new aircraft.

At the outset of the war there were major reservations about what could be achieved through aerial combat. A 1911 declaration by the Institute of International Law had actually banned their usage for anything other than reconnaissance missions, and indeed when the conflict first erupted in 1914 planes were primarily being used to observe enemy movements rather than to attack a nation’s opponents. Some of this was quite significant. In the first weeks of the war British and French reconnaissance planes were able to identify key German movements in northern France and stopped the Germans from possibly striking decisively towards Paris in the opening gambits of the conflict. Similarly, in the most significant engagement of the war in its early stages on the Eastern Front, the Battle of Tannenberg, fought between Germany and Russia in modern-day Poland in late August 1914, German planes played a pivotal role before the Germans’ crushing victory over the Russians.

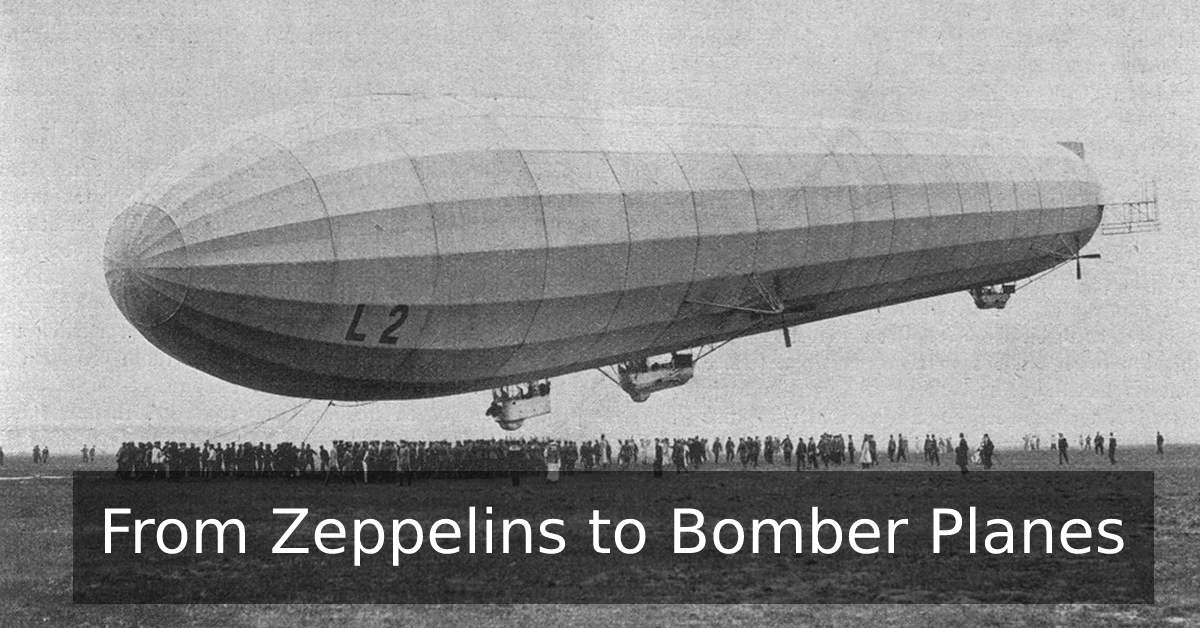

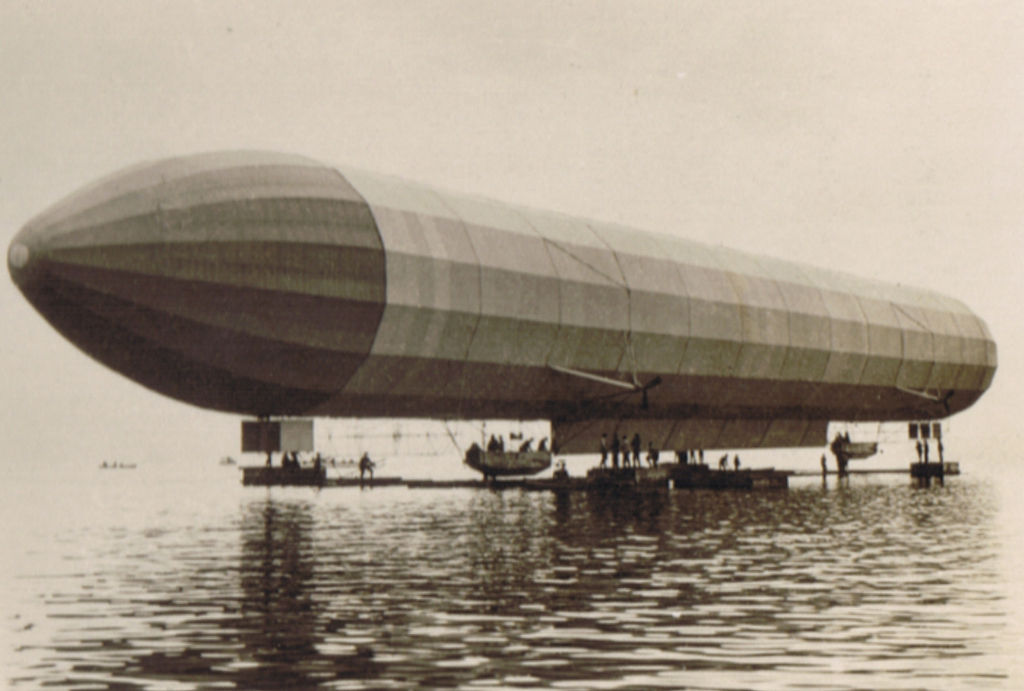

However, the most striking aspect of any kind of aerial combat during the early stages of the war was the use of Zeppelins or air-ships. These were developed in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, based on a design by the German inventor, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, and came into use by the late 1890s and 1900s. Technically Zeppelins were not planes, as they relied on large hydrogen cells to inflate a large fabric covering around a metal frame to float them and drive them, rather than using a battery or engine as the Wright brothers did at Kitty Hawke in 1903. As such they were operating on lighter-than-air technology, rather than heavier-than-air methods. However, the Zeppelins were soon in increasing usage for air travel, particularly from 1910 as Deutsche Luftschiffarts-AG or DELAG for short began commercial flights on Zeppelins.

“A five engined Gotha (Actually a Staaken R.XIV) came over about midnight and dropped a few bombs. The searchlights got him and this time Jerry had a surprise as our flying scouts were up, spotted Fritz at once and went for him. In a few minutes a fight as on and we soon saw the big Gotha (Staaken R.XIV) in flames. He came down and a number of soldiers ran to the burning wreck, when one of the bombs exploded in the heat. Several of those who were near were killed and more injured. This machine carried eight men, three had been shot, four burned and one staff officer had jumped with a parachute, but this failed to open so he too was killed” – Diary of Thomas Spencer

Once the First World War commenced, Zeppelins were soon being employed by the Germans for bombing purposes. This was owing to the fact that the airships were much more technologically advanced by 1914 than the very volatile airplanes which were being utilized for reconnaissance missions. It is generally believed, as a result of the Hindenburg disaster of 1937, when the Hindenburg airship crashed and killed 35 passengers while trying to dock in New Jersey, that the hydrogen fuel cells employed to power these airships were extremely volatile. But this was largely not the case. When Zeppelins were first employed by the Germans to bomb Britain during the First World War, the airships proved quite resistant to counterattacks by standard bullets and shrapnel.

It was only from 1916 onwards when the British began using machine guns and new incendiary explosives and ammunition that the Zeppelins’ weaknesses were exposed. As a result, dozens of bombings were successfully conducted against Britain in the first half of the war. These began in January 1915, starting with raids on the north of England, but from May 1915 the focus of such bombings switched to London. In total, by 1916 hundreds of thousands of pounds worth of damage had been caused by these Zeppelin bombings to key sites throughout England by the German Zeppelins and hundreds of people were killed. But by 1916 the tide had turned. The British counter-attacks had become increasingly effective and by 1917 German efforts to employ their Zeppelins against the British were diminishing.

This change in tactic was also largely caused by developments in the types of airplane which had been used since the war broke out. At the outset of the war, the British had a miniscule amount of heavier-than-air aircraft, while the French had slightly more, and the Germans were focusing their energies on the deployment of Zeppelin bombers. In the course of 1915 and early 1914, however, this pattern was changing. From the early types of reconnaissance planes, sheer necessity in the war effort was leading to the development of different types of planes, some of them bomber planes where bombs could be dropped on the enemy front lines, and some being trench strafers, where quick strikes could be made against the trenches on the various European fronts.

However, perhaps the most significant change was in the development of advanced fighter planes where individual pilots had much greater maneuverability in their planes and were armed with machine guns to strike at other planes. These were increasingly deployed to counteract the actions of bomber planes, trench strafers and reconnaissance planes. As this became the main arena of the aerial combat during the First World War it would be transformed completely from the situation which obtained in the late summer and early autumn of 1914. As a result, from late 1916 onwards fighter pilots like Alfred Ball of the British Royal Flying Corps and Manfred von Richthofen of the Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte,or German Air Force, became pivotal figures in the aerial combat which was occurring on the Western Front as the war entered its most critical period.

As we will see in Part II of this blog the second half of the war saw an increasing level of technological development in the field of aerial combat, such that by 1918 the planes which were flying over the Western Front were immensely different to those which had been used for simple reconnaissance in 1914. But what happened to the Zeppelins? Curiously it was not for another twenty years that use of the German airships in all arenas would come to an end. Transatlantic flights would continue on Zeppelins throughout the 1920s and 1930s, particularly from 1926 onwards when the restrictions on German manufacture of Zeppelins which had been imposed as part of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 were brought to an end. Indeed such was their level of use in the early 1930s that the Empire State Building in New York City included a docking station in its original design. But following the Hindenburg disaster of 1937 airships were gradually abandoned as a viable method of air-travel in favor of safer forms of air transport. Thus, the First World War was pivotal in ensuring the dominance of the airplane as the predominant form of air-travel in the modern age.