The Allied Arctic Convoys (1941 – 1945)

On Sunday the 22nd of June 1941 Operation Barbarossa, Nazi Germany’s invasion of Soviet Russia, was initiated. This was the largest ever invasion campaign undertaken by a nation state against another country and involved three million Axis troops, 600,000 motorized vehicles, 3,500 tanks and over 4,000 aircraft. In the months that followed Germany occupied vast swathes of Eastern Europe through eastern Poland, Ukraine, Belarussia and Russia as far as the cities of Moscow and Leningrad. For a while in the late autumn and early winter of 1941 it appeared as though Hitler’s Germany would defeat Stalin’s Russia. It was in these dire straits that the Soviet leader appealed to Britain for any kind of support it could provide against the German advance. One of the less well known stories of the Second World War is the response of Winston Churchill’s government in sending convoys of supplies and war material through the North Atlantic and into the Arctic where they landed in the White Sea. These provided vital aid to Soviet Russia at the height of the emergency and for years thereafter.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union on the 22nd of June 1941 Churchill and Stalin quickly negotiated the Anglo-Soviet Agreement on the 12th of July. By this the two sides agreed to aid each other in whatever way possible and that they would not enter into a separate peace with Germany without the other. This had some very immediate implications on the international stage, notably the joint Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran in an effort to shore up the Allies’ position in the Middle East against a possible Axis invasion of the region through Turkey. But the Arctic Convoys were the more subtle and ultimately consequential of the outcomes of the Anglo-Soviet Agreement.

The convoys were underway within weeks. The first was Operation Dervish, consisting of six merchant ships carrying large supplies of wool, rubber, tin and even whole Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft. Departing from Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands on the 17th of August, the fleet headed for Iceland first, protected in relays by several ships of the Royal Navy including the destroyer Electra and the anti-submarine trawlers Macbeth and Hamlet. It reached Iceland on the 20th of August, before departing for Russia on a ten day long voyage on the 21st, eventually sailing into the port of Archangelsk on the 31st of August 1941 before returning to Scapa Flow on the 10th of September.

Dervish was just the first of many. In total between August 1941 and May 1945 there were 78 Arctic Convoys dispatched to Russia. These led to 1,400 merchant ships transporting goods and war material to support the Soviet war effort. In general the convoys headed north from Scotland to Iceland or the North Sea, before skirting Norway and arriving thereafter to north Russian ports of Archangelsk and Murmansk. A great proportion of these goods were ultimately used to support the Russians in the Siege of Leningrad which commenced in September 1941 and dragged on interminably until January 1944, at 872 days long one of the longest and bloodiest sieges in the history of warfare. It made complete sense for the supplies received through the Arctic Convoys to be channeled towards the effort at Leningrad given its relative proximity to the White Sea, while Allied supplies to Russia through the Middle East were channeled north to Stalingrad.

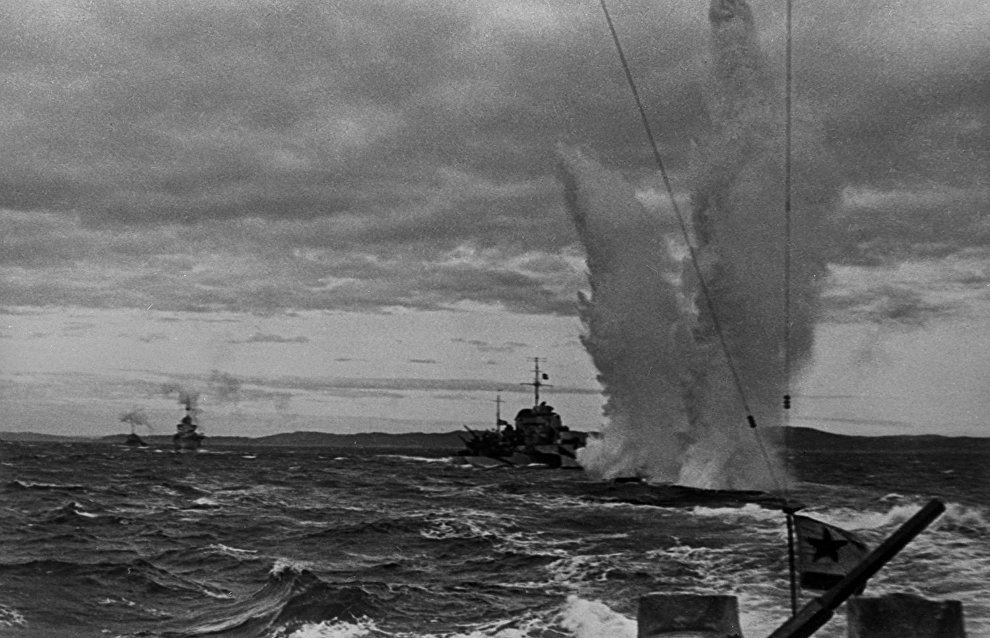

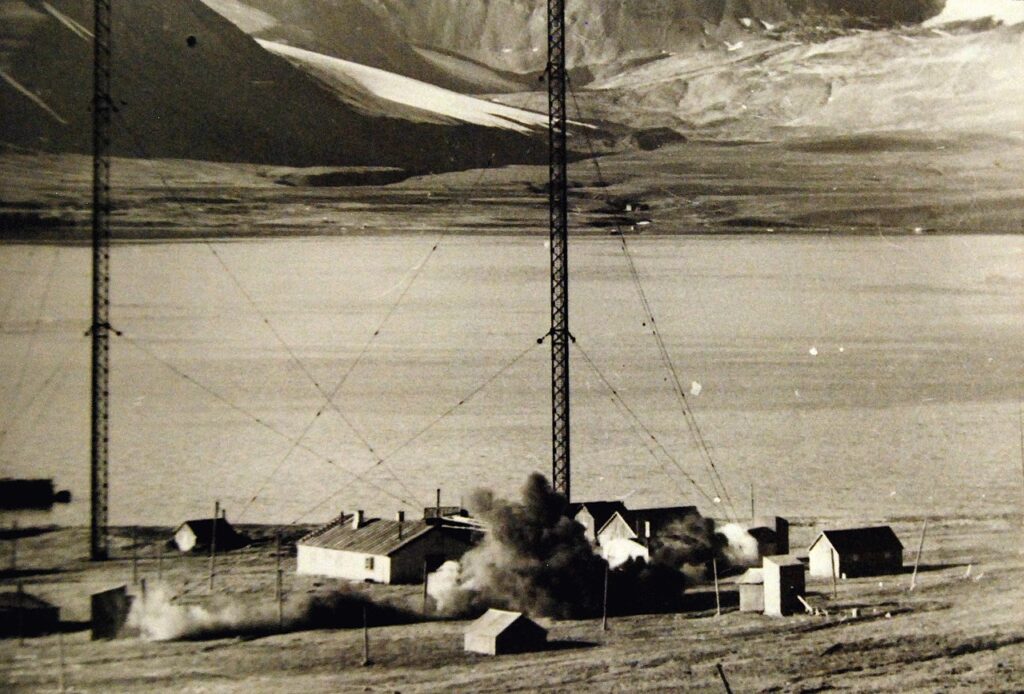

Germany was clear in its determination to try to intercept this passage of vital supplies to Russia from Britain and later the wider network of western Allies. Accordingly the Arctic Convoys and efforts to stop them became part of the wider Battle of the Atlantic, while air attacks were also intermittently launched against the convoys from Axis airbases in Finland and Norway. Norway had been conquered by the Germans in 1941, while Finland had allies with Germany during the lengthy Continuation War of 1941 to 1944 against Soviet Russia.

These efforts to thwart the Arctic Convoys resulted in many significant conflicts, notably the Battle of the Barents Sea on the 31st of December 1942. Through this the Nazis launched Operation Regenbogen to strike against Convoy JW 51B, a convoy of fourteen Allied merchant ships carrying massive amounts of war material, notably over 200 tanks and 2,000 vehicles, with dozens of planes and thousands of tons of fuel. Such was the significance of the material being carried that the British assigned six destroyer class ships to protect the convoy, along with several corvettes and minesweeper and anti-submarine ships. Against this the Nazis sent two heavy cruisers and six destroyers which finally engaged the Allied convoy in the Barents Sea. Despite extensive trading of fire the battle ultimately ended in a stalemate and limited damage to both sides. Both the British and the Germans lost one destroyer and suffered some damage to other ships, as well as the loss of between 250 and 350 men each, but the convoy’s merchants ships made it through to the port of Murmansk relatively unhindered several days later. The main implications of the battle were actually for the Axis. Hitler was so infuriated by the failure of the operation that he forced the resignation of Admiral Erich Raeder shortly thereafter and an emphasis was henceforth placed on using U-boats to attack the Arctic Convoys.

The Battle of the Barents Sea was symptomatic of the failure of the Nazis to intercept the Arctic Convoys. In total nearly four million tones of goods and war material were transported into Russia by the Allies through the Arctic Convoys between 1941 and 1945. Of that ninety-three percent made it safely through. Only seven percent of this was lost to Axis attacks or other losses. The goods which came through in these Convoys constituted nearly one-quarter of the all material support which the Allies provided to the Soviets during the course of the war. The attrition was also relatively limited. In total the Allies lost just 85 merchant ships and sixteen warships over the course of the entire campaign. Thus, there is no doubting the significance of the Arctic Convoys in providing huge support from the Western Allies to Soviet Russia during the course of the Second World War.