The Outbreak of the Italian Civil War and the Gran Sasso Raid (September 12th, 1943)

Most histories of the Second World War include details of the rise of Fascism in Italy under Benito Mussolini, the latter’s alliance with Nazi Germany in the 1930s and Italy’s subsequent role in the war in Africa and the Balkans. But thereafter the Italians are largely forgotten about and the Southern Front which the Allies opened in Sicily in July 1943 treated as a sideshow to the Western and Eastern Fronts. Yet Italy was important between 1943 and 1945. Following the Allied invasion of the south, King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and the fascist regime in Rome quickly removed Mussolini from power on the 25th of July 1943 and placed him under arrest. An armistice was then agreed with the Allies on the 8th of September and this led Germany to have to intervene in the country, sending tens of thousands of troops into the peninsula to continue the fight against the Allies. But if hearts and minds were to be retained in Italy, then the Germans needed to establish some semblance of legitimacy and to that end it was decided that it would be best to rescue Mussolini from captivity and re-establish him as head of the Italian government, one backed by German arms. Here we examine the daring raid which plucked him from captivity.

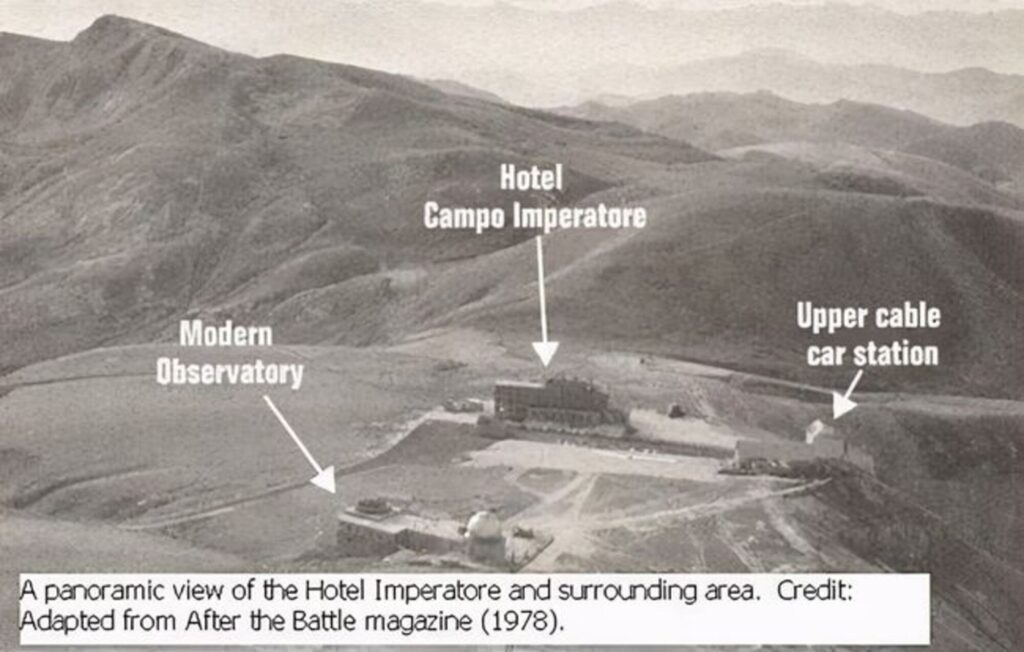

Following his removal from office and arrest on the night of the 24th of July Mussolini was kept captive in various locations around central Italy, but he was eventually imprisoned at the Hotel Campo Imperatore in Gran Sasso, an isolated plateau in the middle of the Apennine Mountains in central Italy. This was an exceptionally remote spot which was only reachable using a cable car to ascend up the plateau. As such it would not easily be assailed, a factor which became crucial once the Germans ordered the invasion of Italy in early September.

As soon as Mussolini had been detained in the summer of 1943, Hitler had given orders in Germany to both the SS and the Luftwaffe to begin planning a rescue mission. Both Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Goering, the respective heads of the SS and the Luftwaffe, were anxious to claim credit for achieving this. The responsibility for carrying out the mission fell to Otto Skorzeny, an Austrian hauptsturmführer within the SS, and Kurt Student, a Luftwaffe general who had overall command of the German fallschirmjäger or paratroopers. Though the two now became rivals to see who could execute the mission successfully they determined to act in conjunction with each other once reconnaissance intelligence had located Mussolini’s exact location at Gran Sasso. Thus, a mission was prepared to rescue Il Duce on the 12th of September 1943.

By the time the mission was launched the Germans had taken control of Rome and the royalists had fled to southern Italy. Consequently the mission was launched from the Italian capital at just after 13.00 hours. The plan was for several Henschel Hs 126 reconnaissance planes to stealthily tow ten DFS 230 gliders to locations near the Hotel Campo at Gran Sasso. Each of these gliders would have nine soldiers as passengers, which were comprised of a mix of Student’s fallschirmjäger and Skorzeny’s SS troops. It was this mixed force of ninety German special operations commandos which touched down on the plateau near the Hotel Campo at 14.05, though one crashed while landing, injuring several of the men. Meanwhile a separate group of paratroopers had captured the cable car base lower down the mountain and had also severed the telephone lines. The garrison of 200 Carabinieri guards above in the Hotel Campo were now cut off in all respects from the outside world.

Despite outnumbering their assailants Mussolini’s captors gave up without a fight. Not a single shot was fired, in part because General Fernando Soleti, a veteran of the Italian African Police, had flown in with Skorzeny and was able to convince the Carabinieri to surrender. As a result, shortly after 14.15 local time, Benito Mussolini was rescued by a mix of German SS and paratrooper soldiers. However, a bizarre episode now followed. A Fieseler Fi 156 Storch plane had arrived once the Hotel had been secured. This was to be used to fly Mussolini out of Gran Sasso, but the event was also to be highly choreographed, with photos taken and video footage captured for use for propaganda purposes throughout Axis Europe. But there was also a contest between Skorzeny and Major Otto-Harald Mors, a fallschirmjäger commander who had overseen the capture of the cable car station lower down the mountain, to claim credit for the success of the mission for both the SS and the Luftwaffe. In an effort to be seen prominently in the photos and video footage being taken Skorzeny now boarded the Fieseler plane with Mussolini. But this was a short take-off and landing plane, one which only sat one or two passengers and could not bear heavy loads. As a result Skorzeny’s decision to board the plane with Mussolini overloaded the Fieseler, which made a dangerous take-off. The propaganda battle between the SS and the Luftwaffe had endangered the success of the mission even after it had succeeded on all other fronts.

Despite Skorzeny’s reckless action the plane made it back to the airbase in Rome and Mussolini was subsequently flown to meet Hitler in East Prussia, via Vienna and Munich. Here the decision was taken to install him as the head of the new Italian Social Republic, with its capital in the town of Salo in northern Italy. He was, though, hereafter a mere puppet. The Allies controlled the south of the country and the islands, while the price of accepting German aid was that Italy’s possessions on the Dalmatian Coast and in the Balkans were taken under German possession or annexed to various other states such as the Independent State of Croatia. From a propaganda perspective the SS were the real victors. Despite the fact that the SS unit had only made up a small portion of the entire rescue team, Skorzeny’s audacious efforts to put himself in front of the camera at Gran Sasso ensured that Himmler, the SS and Skorzeny himself got the credit for executing a mission which even Winston Churchill begrudgingly admitted was ‘one of great daring’.

Below is a video of Mussolini escaping on a Fieseler Fi 156 Storch. He then met with Hitler after the escape.