Britain avoided a direct Nazi invasion in the course of the Second World War. The country was certainly dreadfully impacted upon. The Blitz saw an intensive aerial bombardment of the country by Germany between the autumn of 1940 and the summer of 1941, while intermittent bombings and rocket strikes continued through to 1945. Similarly the Battle of the North Atlantic witnessed shortages of key supplies in Britain and severe rationing throughout the conflict. Further afield, British overseas territories in Malaysia and Burma were invaded and occupied by the Japanese in 1942, while British colonial territories in Egypt and the Middle East were also impacted on. But Britain itself was never invaded or any land occupied. That is except for the Channel Islands. Between the summer of 1940 and the end of the war in May 1945 this chain of islands in the English Channel were held by the Nazis.

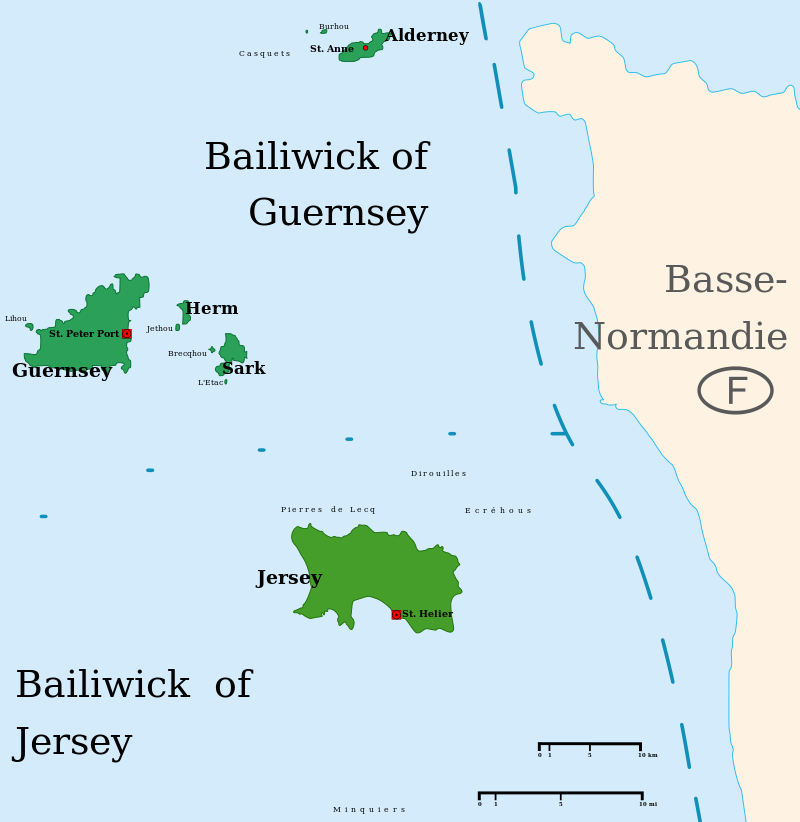

The occupation of the Channel Islands was almost entirely the by-product of its geography. The islands are much closer to France than to England. Indeed Jersey, the largest of the island chain (only Guernsey is of a comparably large size), lies just 22 kilometers to the west of the Cotentin Peninsula in Normandy on the French mainland, the nearest part of Europe to the island. Aware that any effort to retain the islands would have opened the garrisons there to a relentless barrage of naval and air bombardments by Germany once France had been conquered in the early summer of 1940, the British High Command took the decision to strategically retreat from the islands once the Low Countries and France had been largely overrun in May. The Islands were demilitarize in June. One of the evacuees was none other than Brigadier General Charles de Gaulle on the 17th of June on his way to London where he would lead the French Resistance in exile. The governors left the Islands on the 21st of June. Not all of the civilian population could leave, not least because the speed of the Nazi conquest of France had caught everyone unsuspecting and there was now insufficient time to remove the Islands’ total population of about 90,000 people. In the end just approximately 25,000 Islanders made it to Britain, with priority being given to children, older people and younger men who could be enlisted in the British army.

The German occupation was relatively tentative, the Nazis being unaware that the British had demilitarize the islands. As a result on the 28th of June a Nazi squadron bombed St Peter Port on the island of Guernsey and similar raids on Jersey resulted in several dozen civilian casualties. Then the Nazis realized that the Islands had been abandoned. Accordingly, beginning on the 30th of December, several transport planes of German troops began landing on the islands such that by the 4th of July a German military presence had been established on each of the main islands, essentially formalizing the Nazi takeover. Further detachments of German troops arrived by boat from mid-July onwards to further garrison the Islands.

Life in the Channel Islands during the Occupation was harsh. Although a civilian government continued to operate, the Islands were largely governed through a military governor, while the status of the region was symbolised in the introduction of a new ‘Scrip’ or occupation money. The Islands effectively became a frontline for military operations in the English Channel, with radar and other naval and air buildings established here and large naval fortifications as part of Germany’s wider ‘Atlantic Wall’. The only German concentration camps to appear on British soil were also erected on the Islands. Here, forced manual labour, amounting to all intents and purposes to slave labour, was imposed on the civilian population. Over 6,000 people went through these and perhaps as many as 700 lost their lives. Approximately 2,000 Islanders were also deported to mainland Europe, many of them Jews who were sent to the death camps in Central and Eastern Europe.

There was no major resistance movement amongst the civilian population. As a forward base in the Channel there were tens of thousands of German troops stationed here throughout much of the war, such that for every two civilians there was one German soldier. Consequently any attempt at concerted resistance would have stood zero chance of success. Moreover, much of the civilian population who were of a good fighting age had already joined the British army and were amongst those evacuated in 1940. Furthermore resistance would have resulted in reprisals. Hence, as one Islander, a medical doctor by the name of John Lewis, succinctly put it after the war, “Any sort of sabotage was not only risky, but completely counterproductive.”

It might have been expected that the Channel Islands would have been one of the first places liberated when a combined Allied force of British, UK, Canadian, Anzac and Resistance fighters first opened a Western Front in Europe in June 1944. But even after the D-Day landings no effort was made to seize the Channel Islands, the view being that they were so heavily fortified and garrisoned that it was not worth what it would cost in deaths. In any event, with the Allies quickly reconquering northern France and moving towards Paris and west into the Low Countries, the Islands’ supply lines were completely cut off. It was believed that they would soon surrender.

Yet they didn’t. Not for another ten months. In September 1944 an Allied ship sailed out to the Islands to discuss with the Germans there if they were aware that their position was hopeless, however the occupiers refused to discuss surrender terms. Then, in the winter of 1944, with resources at a bare minimum on the Islands, the Allies allowed supply ships of food to sail to the Islands in order to prevent any of the civilian population starving to death while the Nazis continued to refuse to surrender.

Ultimately the Channel Islands were one of the last regions of Nazi occupied Europe to surrender to the Allies. Hitler had killed himself in Berlin on the 30th of April 1945. Then on the 8th of May the Allies accepted the unconditional surrender of Germany. That morning at about 10am the German occupiers informed the civilian population on the Channel Islands that the war was over in Europe. The following day the HMS Bulldog, a British B-Class destroyer ship, arrived at St Peter Port on Guernsey and took the surrender of the occupying German forces, while the remaining Islands were fully liberated in the days that followed. Thus, the Channel Islands were liberated, much the same way as they had been conquered in 1940, without any real military engagement to speak of. Consequently, we might call the liberation of the Channel Islands in 1945 ‘the Bloodless Liberation’.