The Doolittle Raid (April 18th, 1942)

Some military engagements result in victories which are of little strategic military value for the winning side, but which are of immense benefit for the morale and psychology of the victors. Few operations were as significant in this respect as what has become known as the Doolittle Raid. This air attack on the Japanese capital of Tokyo on the 18th of April 1942 by sixteen American bomber planes did little damage to the Japanese war effort, but was of great significance in boosting US morale in the early stages of the country’s involvement in the Second World War. This was sorely needed in the spring of 1942, as the catastrophic Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in Hawaii on the 7th of December 1941 had left Americans feeling vulnerable and demoralised.

Within weeks of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour and the entry of the United States into the Second World War the US military command began considering ways to strike back against the Empire of Japan. This would be a symbolic attack aimed at denting Japan’s sense of invincibility following the attack on Hawaii. Accordingly on the 21st of December 1941 the US president, Franklin Roosevelt, at meeting at the White House ordered the Joint Chiefs of Staff to organise a bombing raid against Tokyo.

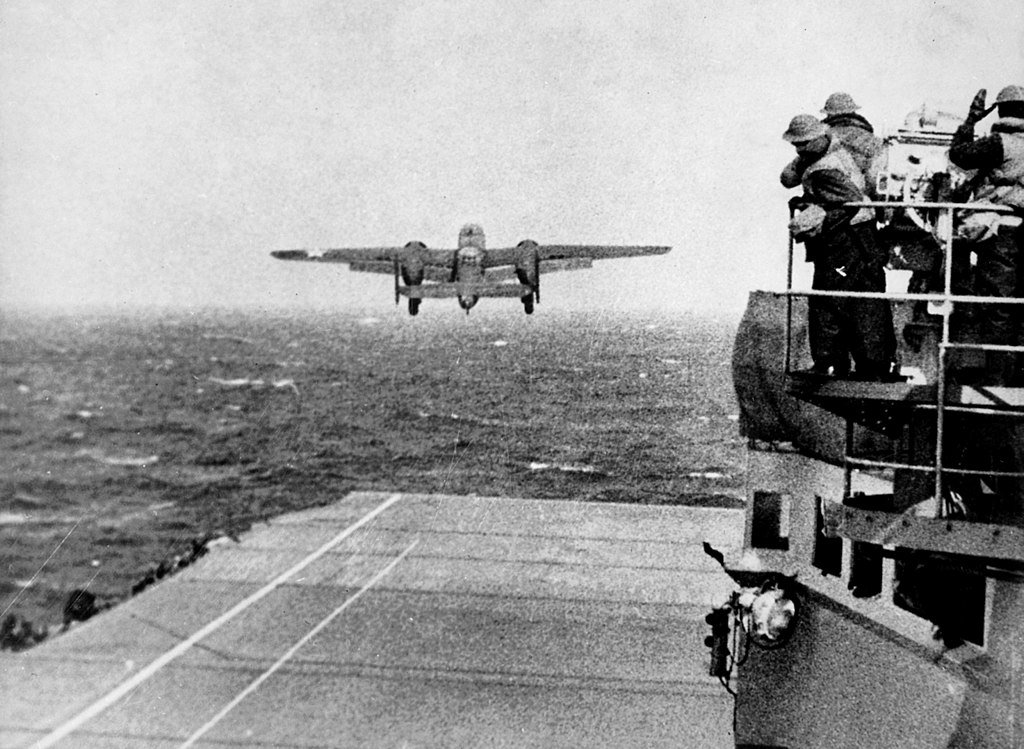

In January 1942 Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle was assigned to command the raid. Weeks of planning and preparation followed. Eventually it was determined that the B-25B Mitchell medium bomber plane could be placed on a US aircraft carrier and successfully take off from it if it was sufficiently lightened. As such in the weeks that followed the B25s were modified to the extent of even removing their radios. Finally, after extensive preparation it was possibly to launch the planes from the carriers, with each carrying four specially constructed 500-pound bombs. To these were attached some Japanese friendship medals which had been given by Japanese servicemen to their American counterparts in the years prior to the war. They were to be returned to Japan. Cameras were also installed on the undercarriage of several of the planes so that the raid could be filmed and broadcast back home for propaganda purposes.

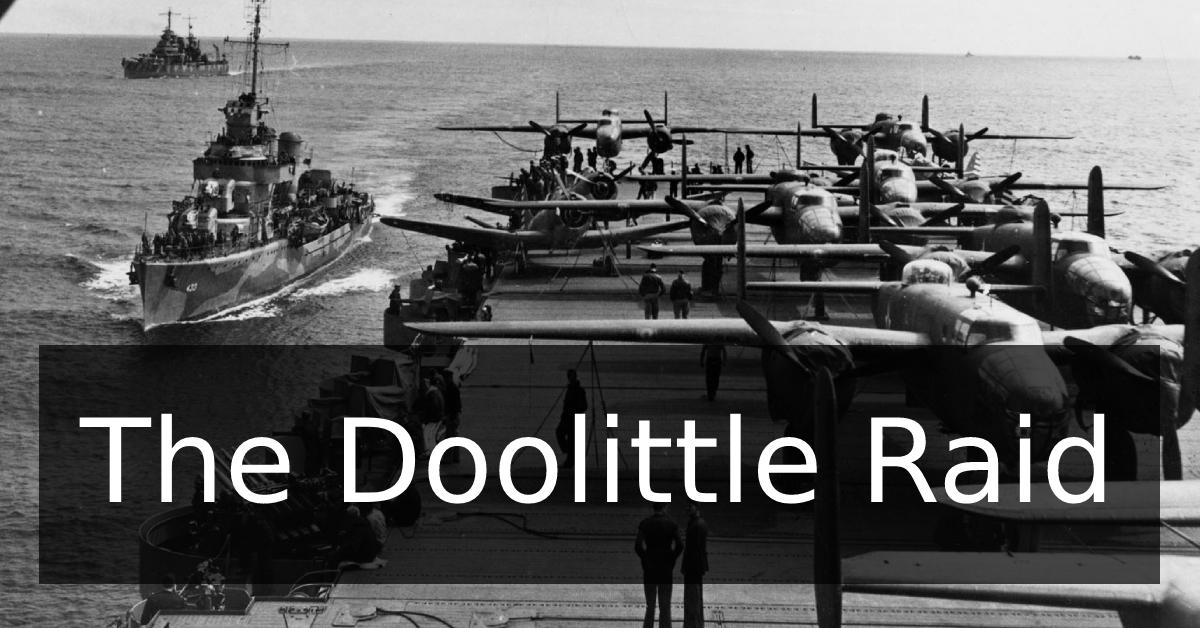

With these preparations made, sixteen of the bomber planes were loaded on the aircraft carrier, the USS Hornet stationed at Alameda Naval Air Station in San Francisco Bay. They would each be crewed by five men, making a mission crew of 80 men. Doolittle would captain the lead plane. On the 2nd of April 1942 the Hornet left the West Coast of America, accompanied by Task Force 18. Several days later it was joined by Task Force 16 and a further carrier, the USS Enterprise, in the Pacific Ocean near the Hawaiian Islands. Thus, it was with a combined fleet of two aircraft carriers, three heavy cruisers, eight destroyers and a number of smaller ships that the fleet set out towards Japan in mid-April.

The plan was to get as close to Japan as possible before the sixteen planes would launch on their raid. However, on the morning of the 18th of April shortly after 7am the small fleet was spotted by a Japanese ship while they were still some 1200 kilometres off the coast of Japan. While the Japanese ship was quickly sunk, it was not before it had radioed the location of the US fleet. Accordingly a decision was taken to launch the planes early, ten hours before the planned launch and over 300 kilometres further out from Japan than had been intended. The sixteen aircraft launched successfully between 8.20am and 9.19am on the morning of the 18th of April. The Doolittle Raid was underway.

In total it took nearly six hours for the bomber planes to reach their target in Tokyo. They began arriving there shortly after midday local time, having crossed several time-zones. That lunchtime they bombed ten specifically selected military and industrial sites in Tokyo, while some planes spread out to attack sites in Osaka, Yokohama and elsewhere. Incredibly only one of the sixteen planes was damaged by enemy fire before reaching their targets, though a second had to jettison its bombs early after a gun turret malfunctioned.

Having delivered the payload the bomber planes and their crews continued westwards. It had never been the intention to turn around and try to return to the fleet in the Pacific. Rather an arrangement had been reached with the nationalist rebels in Japanese-occupied China that the planes would fly to China, where they would bail out and receive aid from the nationalists led by Chiang Kai-Shek. Most of the planes made it to the Chinese coast, though they barely had enough fuel left over to do so. In total the crew of fifteen of the sixteenth planes were able to either crash land in China or bail out of their planes near the Chinese mainland. One plane landed in the USSR, where they were interred by the Russians who were not yet at war with the Empire of Japan. Of those who landed in China, two crews were captured by the Japanese. Several of these were subsequently executed by firing squad. Most of the others who landed in China were aided by the Chinese nationalists and made it back to America in the weeks and months that followed.

Of the 80 crew members who undertook the mission, only three were killed in action and 69 escaped capture or death. When Doolittle made it back to the United States he expected to be court martialed, believing the raid had been a failure owing to the loss of all the planes and the minimal strategic damage inflicted by the bombing. He was to be surprised. While the raid had inflicted little material damage on Tokyo or the Japanese war effort, morale in the US soared when news of the Doolittle raid was released. Doolittle himself was promoted to Brigadier General and presented with the Medal of Honor, while 80 crewmen who had undertaken the raid were awarded with the Distinguished Flying Cross. Thus, the Doolittle Raid, while of limited strategic value from a military perspective, was a considerable victory for morale in the dark early days of the US’s involvement in the Second World War.