One of the classic films based during the Second World War is Where Eagles Dare. Released in 1968 and starring Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood, the film tells the story of British and American special operatives disguised as German soldiers sneaking into a Nazi stronghold high up in the Bavarian Alps. Their goal is to rescue an American agent who has key plans relating to the planned Allied invasion of France. The story is entirely fictional and no such mission was ever undertaken, but the set-up of a Nazi stronghold high up in the mountains is closer to reality than one might think, for the Nazi leadership did indeed have such an Alpine retreat. Indeed the Berghof was more central to the politics of the Third Reich than one might think.

Hitler had always had an affinity for the Alpine region. It was here on the Austrian side of the German-Austrian border that he was born at Braunau am Inn in 1889. The Nazi Party was effectively a Bavarian political party before it became a German one and the Alps straddle the southern parts of Bavaria. Indeed, after he became Nazi leader and once he was released from Landsberg Prison late in 1924 Hitler began vacationing regularly at Berchtesgaden, the Alpine region in the extreme south of Germany. He subsequently purchased a house here, high up in the mountains with money from the sales of his rabidly Anti-Semitic, paranoid conspiracy theory-laden political manifesto, Mein Kampf. Then, following his rise to power as Chancellor of Germany in 1933, he employed the architect, Alois Delgano, to renovate and expand the chalet into a grand mansion. This would subsequently become known as the Berghof, meaning ‘Mountain Court’, but to most others it was known as the ‘Eagle’s Nest’.

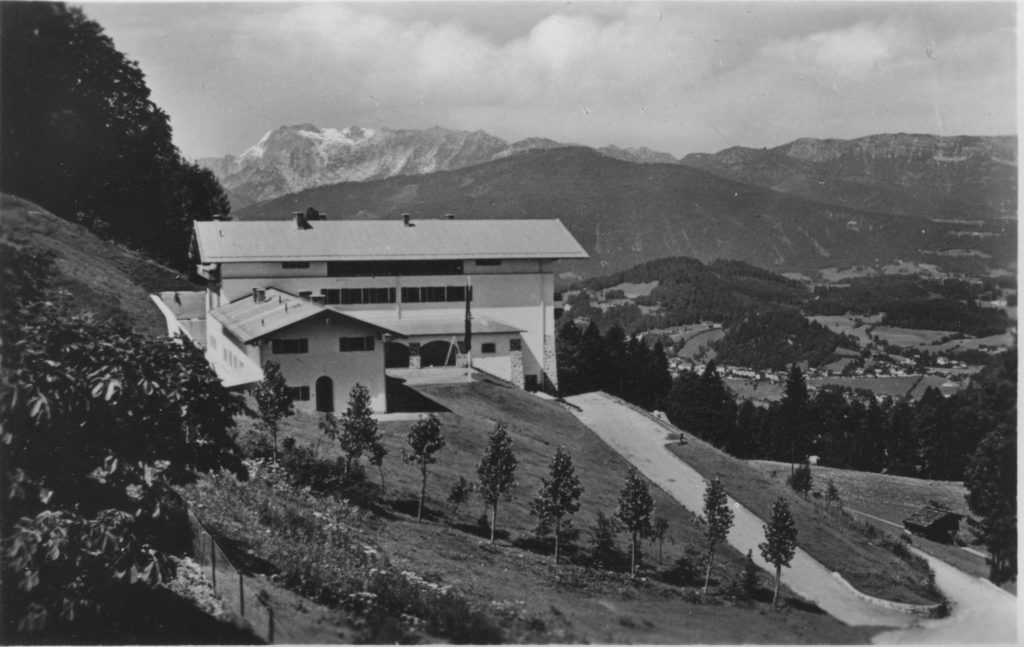

When it was complete the Berghof towered 3,000 foot above ground looking out over Bavaria and Austria. Extensive rooms were laid out for Hitler and his partner Eva Braun and visiting guests. A great hall was expensively decorated with eighteenth-century furniture to entertain guests, while Renaissance paintings and Baroque ornaments were purchased for the entranceway and other rooms. The most impressive section was the large terrace with its panoramic view of the Alps and Bavaria. And the Berghof was not the only building constructed here. Local landholders were forced to sell their properties so that other senior Nazis could build their own mansions nearby. An airstrip was even constructed so that small planes could fly the Nazi leadership in from Berlin, while an elevator was built to convey individuals from the Eagle’s Nest down the mountain to the town of Berchestgaden, the latter of which effectively became a service town for the Nazi settlements towering above it.

Hitler was fond of keeping his quarters outside of Berlin. For instance, during the Second World War he based himself in the Wolf’s Lair, a massive bunker in western Poland, rather than in the German capital. Other than the Wolf’s Lair, the Berghof was his favored haunt. As such, it became the site for many high level diplomatic meetings over the years. When the Austrian quasi-dictator, Kurt von Schuschnigg, was attempting to prevent the union of Germany and Austria early in 1938 he met with Hitler at the Berghof. Seven months later it was the turn of the British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, as he sought to prevent German annexation of the Sudetenland. Other guests to the Berghof included the Aga Khan, David Lloyd George and Benito Mussolini. Hitler also convened a meeting of his generals here in the late summer of 1940 at which he first instructed them to begin drawing up strategic plans for the invasion of Russia.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given how much time he spent here, the Berghof was also associated with several efforts to assassinate Hitler. The German army captain Eberhard von Breitenbuch arrived there with a concealed gun on the 11th of March 1944 with the intention of killing the Fuhrer, but he could not obtain an audience with him. Claus von Stauffenberg originally intended on planting a bomb here to assassinate Hitler in June 1944, before eventually doing so at the Wolf’s Lair on the 20th of July. The British also planned to assassinate Hitler here in Operation Foxley, a plan whereby snipers would parachute into Austria and then traverse the mountains to the Berghof, killing Hitler from afar during his twenty minute daily exercise routine. However, before this was decided upon Hitler stopped visiting the Berghof and increasingly ensconced himself in either the Wolf’s Lair or the Chancellery bunker in Berlin.

In the spring of 1945, as the Russians edged towards westwards towards Berlin, many of Hitler’s confidantes urged him to abandon the German capital and head for the Alps, where a last stand could be made in the mountains around the Berghof. Some even hoped that if they held off for long enough the Western Allies and the Soviets would end up falling out with each other. But Hitler was adamant he would stay in Berlin and it was there he killed himself on the 30th of April 1945. Most of the other Nazi leaders headed north-west to the border with Denmark where there were few Allied troops and where they formed a temporary government. But Goering did go south, armed with a briefcase full of the opiates he had been addicted to for over twenty years. He floated in around the Berchtesgaden area in late April, but eloped over the border to Austria eventually as American troops neared the Berghof.

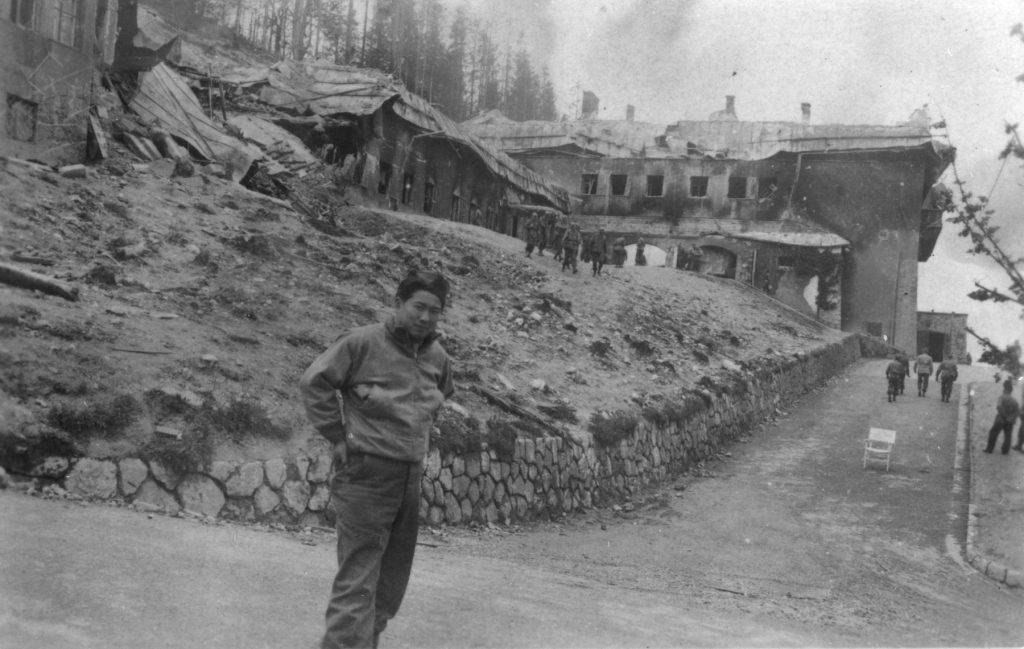

Eventually it was the 7th Infantry Regiment of the US 3rd Infantry Division which arrived to Berchtesgaden first. They got there on the 4th of May, but they didn’t head right up the mountain to the Berghof. It was the French 2nd Armoured Division that did so shortly afterwards. There they made an astonishing discovery, a wine cellar under the Berghof, which was replete with approximately half a million bottles of fine wine, champagne and cognac. Word spread quickly and by the afternoon of the 5th of May Allied divisions were arriving to the Berghof to fill their trucks, tanks and whatever else could be filled with wine bottles. The elevator to the mountain side retreat was broken, so a medical unit was even brought in to stretcher casks of wine up and down the hillside to a car park below. By the time Victory in Europe was announced on the 8th of May 1945 there were many sore heads already in southern Germany.

While the wine cellar was intact, the Berghof itself and some of the surrounding houses and buildings had been badly damaged by Allied bombings in late April 1945 and then the SS had set fire to sections of it before abandoning it in the face of the approaching Allies in early May. Thus, it was already quite damaged by the time the war ended. Nevertheless, a decision was made by the Americans, in whose zone of occupation it was located after the war, that it should be destroyed, along with the houses located there of other Nazi leaders such as Goering and Bormann. This was to avoid the site becoming a neo-Nazi shrine in years to come. Thus, in 1952 by order of the German government the last of the building’s shell was destroyed.