The Development of Aerial Combat during the First World War – Part II

As we saw in Part I of this discussion of the development of Aerial Combat during the First World War the first years of the conflict between 1914 and 1916 were a formative period during which the major powers experimented with very many different types of aerial combat. This ranged from use of very primitive airplanes on the fronts in 1914 for reconnaissance purposes to the use of Zeppelins or airships to bomb the enemy, principally by the Germans. Here we explore the latter half of the war when recognizably modern aerial warfare began to emerge with fighter planes and bomber planes being brought into use, particularly on the Western Front.

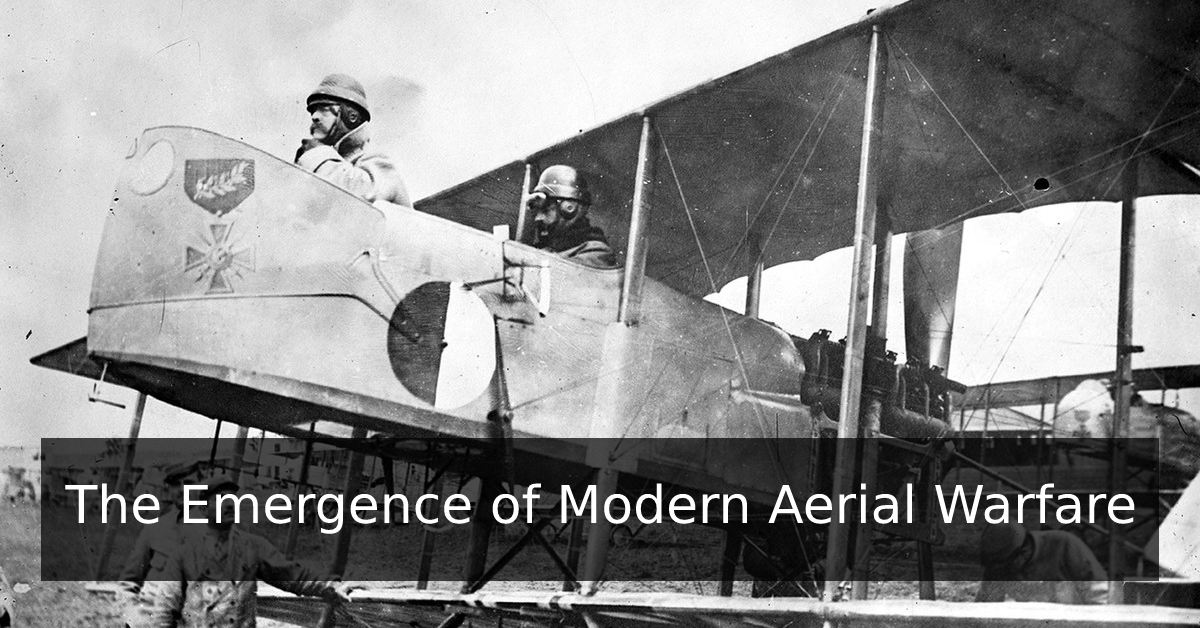

The first major development in the advent of modern fighter planes occurred in 1915 when a Dutch aviation pioneer by the name of Anthony Fokker helped design a new plane for the German air-force. Named the Fokker E.I. it was the first aircraft to enter service which had a synchronization gear. This allowed for a machine gun to be fired through the arc of the propeller of the plane, effectively equipping fighter pilots with a machine gun in the skies. The Fokker E.I. was first deployed over the Western Front in northern France on the 1st of July 1915. With this new ability to rapidly fire on enemy planes in the skies over northern France the Germans achieved air superiority with the Fokker E.I. for the second half of 1915. As a consequence of ‘the Fokker Scourge’ the British and the French were driven to improve their own air-force, resulting early in 1916 in the development of the Nieuport 11, a French-designed fighter plane which had a Lewis machine gun mounted at the front. In a slight variation on the Fokker E.I., this French technology allowed uninterrupted fire over the propeller of the plane, rather than through its arc. Deployment of the Nieuport 11 from January 1916 onwards brought ‘the Fokker Scourge’ to an end and henceforth the Allies and the Central Powers were on a relatively even footing in terms of aerial combat.

As a result of these developments in aerial combat, by mid-1916 both sides were forming elite groups of fighter pilots. Many of the individuals involved, known as flying aces, gained major notoriety for the number of enemy planes they brought down. A good example amongst the British was Albert Ball. Originally an infantry man in 1914, Ball transferred to the burgeoning Royal Flying Corps in 1915. Over the next two years, as the quality of the fighter planes being deployed on the Western Front improved, Ball was victorious in 44 aerial conflicts. However, his career mirrored that of many flying aces in that he was shot down and killed in May 1917. Others, such as Billy Bishop, a Canadian flying ace who clocked up 72 victories between December 1915 and the end of the war, survived.

However, unquestionably the most famous flying ace of the First World War was Manfred von Richthofen. Hailing from a German baronial family, von Richthofen was originally a member of the German cavalry, but transferred to the nascent air-force in 1915. He quickly gained a reputation for his skill in aerial dogfights and by 1916 he had been placed in command of Jasta 11 (Fighter Squadron 11) and was then subsequently given control of Jagdgeschwader 1 (Fighter Wing 1), comprising four full squadrons. Over the next two years Jagdgeschwader 1 and von Richthofen would gain wide notoriety for their effectiveness as an aerial squadron and the brashness of their appearance. Von Richthofen painted his plane in bright red colors, leading him to become known as ‘the Red Baron’, while the pilots he commanded painted their planes as well, leading to Jagdgeschwader 1 becoming known as von Richthofen’s Flying Circus. He was known and respected by both sides for his daring. On one occasion von Richthofen was shot down over the Western Front, but having crashed relatively unscathed he was back in the skies later that day in another plane. The Red Baron, however, was eventually shot down over the Somme on the 21st of April 1918. By that time he had clocked up at least 80 combat victories and was widely regarded by both sides as the ace of aces.

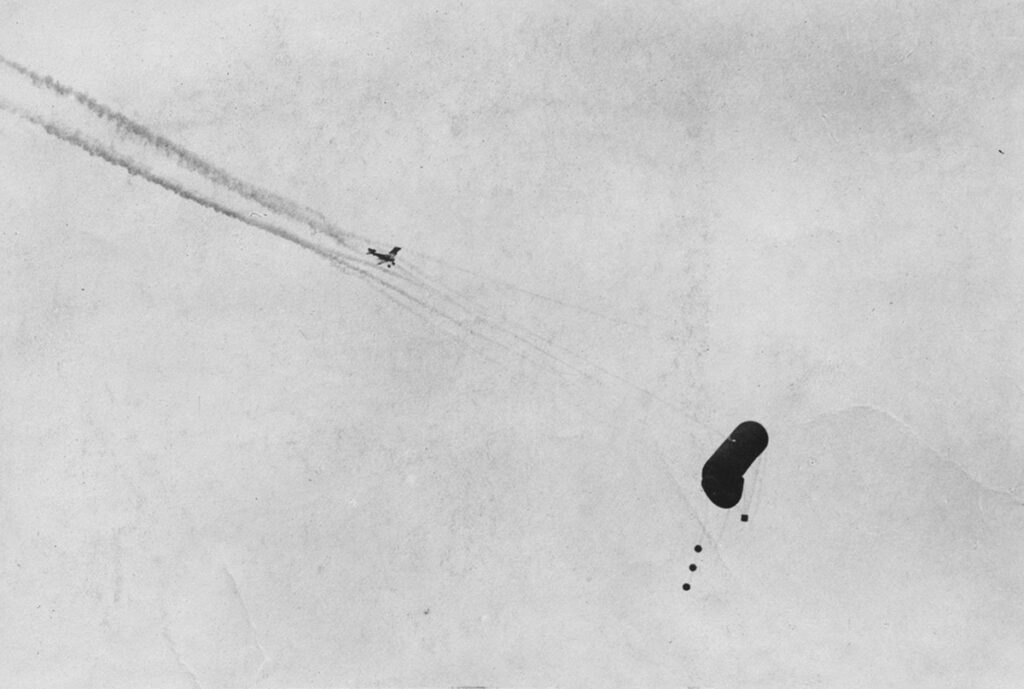

Beyond the development of the fighter planes being used on the Western Front and elsewhere at this time, the final years of the war were very noteworthy for the emergence of effective bomber planes. These were largely being produced in the course of 1916 and 1917 as a means of potentially breaking the impasse which had developed on the Western Front. Unable to do much more than claim a few kilometers of wasteland in northeast France, even through major initiatives such as the Somme Offensive, both sides turned to bombing raids as a means of breaking through the front lines. These entered particular use from 1917 onwards as the Zeppelin airships which the Germans had been employing on bombing missions fell out of favor. In particular with the developed of the Gotha G.V. bomber in mid-1917 the Germans began to rely on this particular model for their bombing raids on the Western Front and on England. They were beginning to prove highly effective by 1918 and 73 tones of bombs were dropped over England by the end of the war by the Gotha bombers. Ultimately, however, they could not change the course of the war by that time and the development of bomber planes in the final stages of the First World War ultimately has more significance for the Second World War than its predecessor.

Overall, then, the First World War had seen a striking evolution in the nature of aerial combat. At its outset in 1914 planes of any kind were something of a novelty for the armed forces of all sides, used for little more than reconnaissance missions. As a result the major powers did not really even have dedicated air-forces and favored the use of Zeppelins and airships for bombing missions. However, between 1915 and 1917 this all changed. Rapid developments in the kind of fighter planes available to both sides saw machine guns being deployed in the skies above the Western Front and flying aces emerge on both sides. Perhaps most consequentially new bomber planes were being developed towards the end of the war, ones which would make the Zeppelins and airships effectively obsolete in the years to come. As such the First World War was the cauldron in which the basics of modern aerial combat were forged.