The True Story of the Attempted Escape from Stalag Luft III (24–25 March 1944)

Ever since 1963 western film-viewers have been aware of the infamous break-out of Allied prisoners-of-war from the Stammlager Luft III POW camp in south-western Poland. Yet while The Great Escape starring Steve McQueen served to immortalise a version of the story, the true story of the attempted escape from what was more widely known as Stalag Luft III was quite different to what John Sturges’s film suggests.

Stammlager Luft III, literally meaning Main Camp, Air III, had been established in March 1942 as a prisoner-of-war camp for captured Allied air-force men near the town of Zagan in what is now south-western Poland, but which at the time was near the centre of the German Third Reich. Initially the camp only held British Royal Air Force officers as prisoners, though this included people from other countries such as Canada, Australia, Norway and Poland who were flying with the RAF during the war. As the war continued, however, the camp expanded in the course of 1943 to include US POWs. Eventually there were nearly 11,000 British and US air-force POWs and their allies being held here in small cabins where they were housed in triple-deck bunks. There was a modicum of civility to the camp. For instance, the prisoners had access to a library and even published their own newspaper. However, there were stringent measures in place to avoid any prisoners escaping. Guard towers surrounded the camps and microphones were set up around the perimeter to detect the sound of tunnelling.

Photo Credit: Wikigraphists of the Graphic Lab (fr).

Despite these preventative measures escape efforts were perennially being undertaken by the Allied POWs. One such effort occurred in October 1943 when three prisoners, Lieutenant Michael Codner, Lieutenant Eric Williams and Lieutenant Oliver Philpot, managed to escape through a tunnel which had been dug out over a three month period under a gymnastic vaulting horse. The trio eventually made their way back to Britain. In its own way this rather modest escape effort was even more successfully than the more famous escape which would take place the following spring.

The Great Escape of 1944 was being planned as early as March 1943, led by RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bushell. While other previous escape attempts had been limited in scale, Bushell wanted to try to get 200 POWs out and the effort would eventually involve over 600 of the camp’s prisoners. Three tunnels were put under construction, codenamed Tom, Dick and Harry. Tom was found by the Germans while being dug and was dynamited. Dick was planned to open into an area which the Germans began clearing for a new camp late in 1943 and had to be abandoned, but Harry would ultimately prove successful.

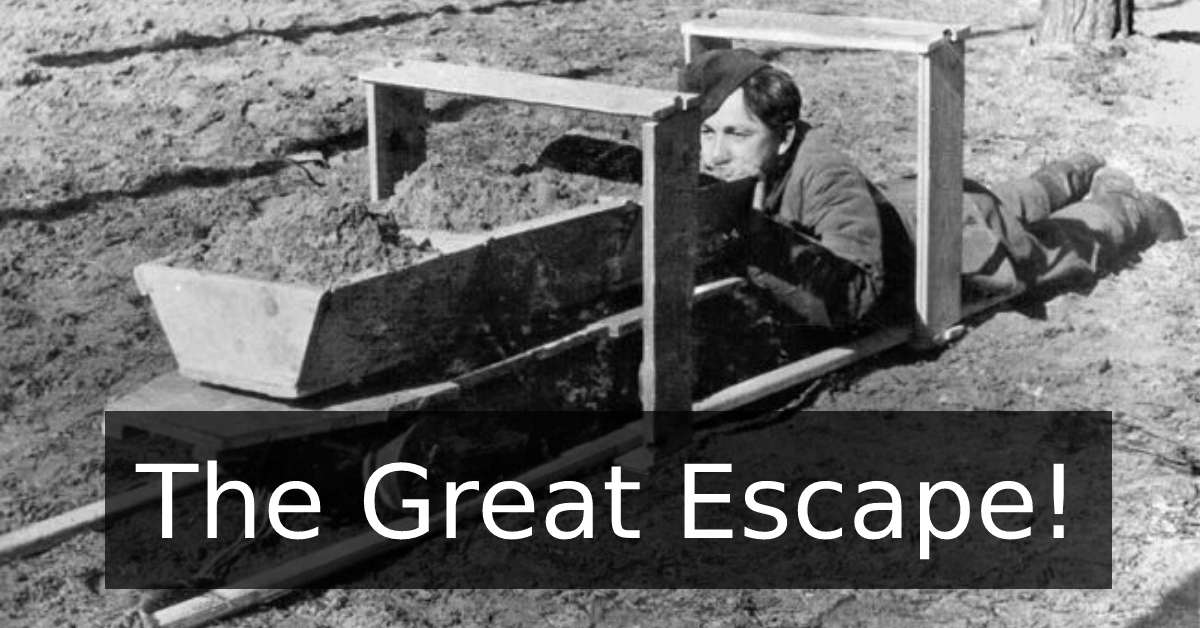

Harry began in Hut 104 where the entry to it was hidden under a stove. The tunnel was dug nine metres underground. It was extremely tight and individuals had to climb through a tunnel which was little more than half a metre wide in places, making for a wholly claustrophobic experience. The walls of the tunnel were supported using wood which was scavenged from all over the camp, much of it being planks taken from the bunk beds of prisoners. Small chambers were constructed at intervals along the tunnel and here pumps were installed to pipe in fresh air. The sand and mud which came out of the tunnel was discreetly deposited around the main yards of the camp by the POWs. Even so the Germans knew something was amiss and had been conducting regular searches of the POWs huts to locate a tunnel, but never found the entry to Harry.

Eventually the tunnel was complete in March 1944. The film of 1963 depicts the POWs as making their own fake German identity papers and other documentation for use once they escaped and were making their way through German-occupied Europe, but in reality the POWs at Stalag Luft III had a great deal of help in producing these from many German soldiers at the camp who were opposed to the Nazi regime. Of the over 600 men who had helped in constructing the tunnel, only 200 were selected to escape. These were chosen based on a number of criteria, one of the principal ones being an ability to speak German, as those who could do so would have the best chance of avoiding capture in the days and weeks after they left the camp.

Eventually the night of the 24th of March was chosen for the escape. This was a relatively spontaneous decision as Bushell and his men were waiting for a particularly dark night so that they could avoid detection. A number of setbacks quickly ensued. For instance, the tunnel opened out into a forest beyond the camp, but this was closer to a guard tower than expected and the POWs had to leave slower than planned. Moreover, the trap door had frozen shut, delaying proceedings by over an hour. Accordingly, only 76 men had made it out by 4.55am. With the sky getting brighter, the 77th man was spotted by the guards at this time, just shy of 5am.

Once the alarm was rang the camp guards quickly began searching the huts, though the tunnel entrance was so well disguised that it took some time to find it, even after Hut 104 was searched. Meanwhile the escape attempt was quickly crushed. 73 of the 76 men who escaped were eventually recaptured in the surrounding region. Only three, two Norwegians, who had flown for the RAF, Pers Bergsland and Jens Muller, and one Dutchman, who had also been an RAF pilot, Bram van der Stok, escaped successfully. The two Norwegians made it to Sweden, while van der Stok eventually travelled to Spain. Of the 73 who were apprehended 50 were executed in reprisals, while most of the other 23 were sent back to Stalag Luft III. The victims included 20 Brits, six Canadians, six Poles, five Australians and people from several other Commonwealth and Allies countries.

Thus, the Great Escape was a slightly different affair to that depicted in the film of 1963. Yet it wasn’t the last escape attempt. No sooner had Harry been filled in and destroyed by the camp authorities, but a new tunnel, codenamed George, was being dug. In the event, it was never used. On the 27th of January 1945 Stalag Luft III was liberated by the advancing armies of Soviet Russia.