The great majority of attention generated by the Second World War is usually focused on Europe and the Allies’ efforts to first combat German expansion and then begin rolling back their earlier conquests from 1942 onwards. This is understandable to a certain extent. After all the other great theatre of the war, the Pacific front, was deliberately made a second priority by the Allies until such time as the war in Europe had been won. Moreover, when attentions did focus on the Far East in the summer of 1945 the advent of the nuclear bomb ended the Pacific War very quickly. But the Pacific War was crucial all the same. One of the most neglected aspects of its history is efforts by the Allies to break out of Japanese POW camps between 1942 and 1945, for the war in the Pacific produced a ‘Great Escape’ that was every bit as dramatic as the escapes from European POW camps such as Stalag Luft III. This was the infamous raid on the Cabanatuan POW camp in the Philippines on the 30th of January 1945.

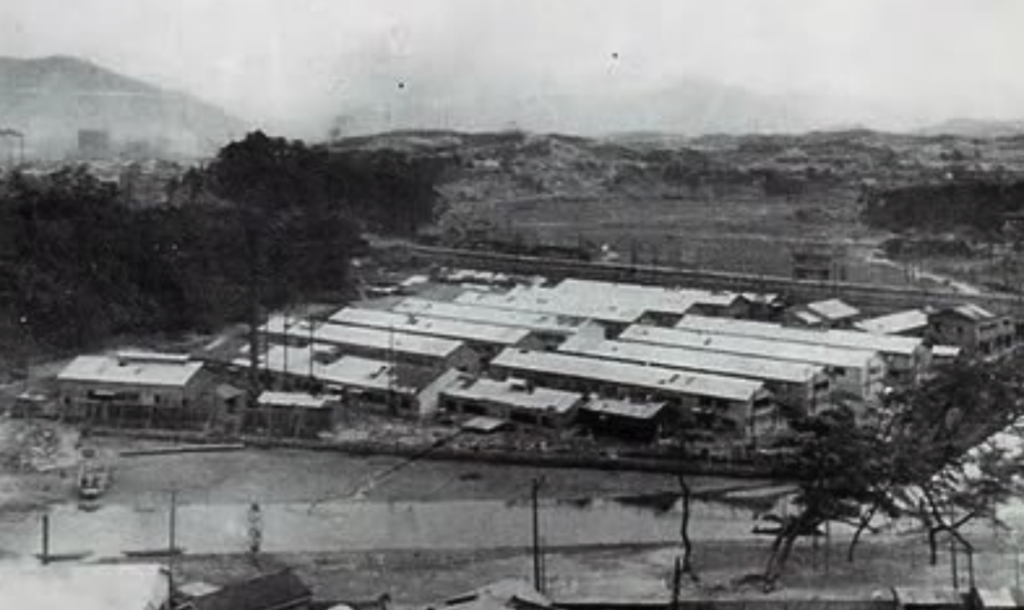

The US-controlled Philippines in Southeast Asia were attacked by the Japanese simultaneous with the strike against the American Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbour in Hawaii on the 7th of December 1941. However, while the strike on Pearl Harbour was a hit and run attack designed to destroy as much of the US’s military capabilities in the Pacific as possible before retreating back to Japan, the assault on the Philippines was sustained and had the goal of conquering the archipelago from the Americans. This was achieved in early April 1942 when the US pulled much of its forces out and the remaining remnants of their armies surrendered to the Japanese onslaught. When they did so over 70,000 American and native Filipino soldiers were captured by the Japanese. Several thousand of these were subsequently transferred to a POW camp established near the town of Cabanatuan on the primary Philippine island of Luzon. Here they would spend much of the next three years.

Conditions at Cabanatuan were severe. Thousands of prisoners had been killed in a brutal death march to the camp in 1942 and this continued thereafter with upwards of 3,000 POWs perishing at the camp between the summer of 1942 and late 1944, the result largely of severe overcrowding and outbreaks of disease. Then as the war effort turned against Japan in 1943 rations to the POWs at Cabanatuan were cut drastically. By the end of 1944 not much more than 500 POWs were still held here. Thus, when US forces invaded the island of Luzon on the 9th of January 1945 under General Douglas MacArthur, the same commander who had been in charge of the military campaign in the Philippines back in December 1941, the liberation of the Cabanatuan POW camp was made a priority. This was especially necessary as the Japanese had begun massacring POWs in other camps as they lost control of islands across the South Pacific in 1944 and early 1945.

A plan was soon formulated for a raid on the camp at Cabanatuan. The 6th Ranger Battalion, which was under MacArthur’s control in the Philippines, had extensive experience of acting as special operatives behind enemy lines. As a result they were selected to undertake a stealth attack on the camp at Cabanatuan some 30 miles behind enemy lines. Just over 130 troops from the 6th Ranger Battalion would undertake the mission, aided by over 250 Filipino guerrilla soldiers. The 29th of January was fixed for the date of the Philippine Great Escape.

The 6th Ranger Battalion set off from American lines on the 27th of January towards Cabanatuan. They had extensively studied maps and charts detailing the layout of the camp and the troops there as well as the surrounding region in the days prior to setting out. Consequently they were able to proceed unmolested to within five miles of the Cabanatuan POW camp by the 29th of January where they rendezvoused with the Filipino guerrillas. At this stage, owing to news of extensive Japanese troop movements in the region, they decided to delay the raid for 24 hours. Consequently it was the 30th of January before the Raid on Cabanatuan was initiated.

The raid began when the Filipino guerrillas severed the phone lines into the camp from Manila. The two main roads leading in and out of the camp were then blocked to prevent any reinforcements arriving. Then the mission into the camp proceeded. It had been arranged for a P-61 fighter plane to fly over the camp to distract the guards with the threat of a bombing mission. The camp was guarded by just over 200 Japanese, but speed was of the essence, as there were approximately 1,000 more Japanese in the wider vicinity and if news of the raid reached the town of Cabanatuan itself there were upwards of 8,000 Japanese stationed there ready to pounce.

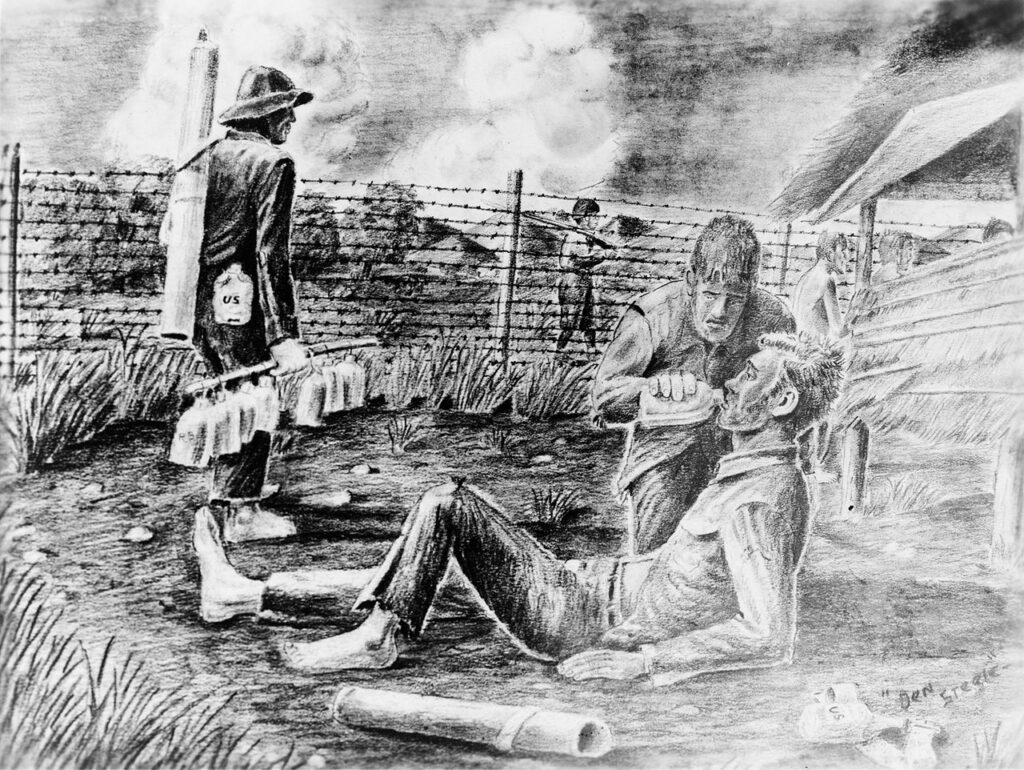

While the camp guards were briefly distracted by the flyover the 6th Ranger Battalion and some of the Filipino guerrillas crawled forwards and entered through the front and back gates of the compound. During this action the Japanese were taken completely unawares and most of the camp guards were quickly overpowered. A difficulty arose when the POWs refused to cooperate with their rescuers, briefly believing that the commotion had been caused by a retreating Japanese battalion who were intent on massacring the surviving POWs on their way through. Once the confusion was alleviated, though, the 6th Battalion and the Filipino guerrillas were able to flee the camp with over 500 POWs in tow.

By now the wider Japanese forces in the area were aware that something was occurring at the POW camp and hundreds of troops were closing in on the Americans, their allies and the prisoners. What followed was one of the most daring escapes ever achieved in the annals of military history. Over the course of the next 24 hours the 6th Ranger Battalion led their convoy all the way back towards the American lines, while under regular Japanese fire. Two members of the 6th Battalion were killed and a handful or so of Filipino guerrillas and POWs were also killed or wounded, but this paled in comparison with the Japanese death toll. Over 500 Japanese troops lost their lives during the raid, while 511 POWs were rescued in total. Thus, the Raid on Cabanatuan proved to be a far more comprehensive escape of POWs in the Pacific theatre than was generally achieved anywhere on the European front during the Second World War.