What has been termed The Greatest Raid of Them of All took place on the 28th of March 1942 at the height of the Second World War. This was the St Nazaire Raid, an amphibious attack by Britain on the port of St Nazaire at the mouth of the River Loire in western France, where it pours out into the Bay of Biscay. At the time in 1942 the port contained one of the biggest dry-docks in the world, the Louis Joubert dry-dock. This was an important asset for Nazi Germany, as it allowed their naval ships to stop here for repairs rather than having to cross through the heavily patrolled English Channel to get to the German ports on the North Sea. Destroying the port would have provided the British with a considerable tactical advantage, particularly so as it was one of the few dry-docks available to the Germans where their new flagship the Tirpitz could have repairs carried out if it was to be sent into active duty in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The plan for the raid, codenamed Operation Chariot, began to be formulated late in 1941. Eventually a scheme was developed whereby a lightened British destroyer-class ship would be sailed to St Nazaire loaded with explosives and then rammed into the gates of the dry-dock. Commandos on board the destroyer and a number of support boats would then disembark and proceed to destroy as much of the nearby installations such as the searchlights, gun emplacements and submarine pens as possible. With this accomplished, the explosives on board the ship would then be detonated on a timer, destroying the dry-dock at St Nazaire and decommissioning one of the Nazis’ most significant ports for the duration of the war. Though some reservations were expressed by Winston Churchill and other military commanders when the plan was revealed to them Operation Chariot was nevertheless given the go ahead on the 3rd of March 1942.

Things moved quickly thereafter. The raid was planned by British Combined Operations HQ for the night of the 27th of March into the morning of the 28th. To execute it the planning team obtained the HMS Campbeltown, formerly the USS Buchanan, an American-built destroyer class ship which had been given to the British as part of the Destroyers-for-Bases aid program with the United States in 1940. The ship was loaded with 4.5 tons of amatol high explosives set and hidden in concrete. It would be manned by 75 men and was to be accompanied by an additional 18 smaller vessels, mostly small motor launches transporting just under 550 other men. Thus, with this small flotilla and just over 600 special operations commandos on board, led by Royal Navy Captain Robert Ryder, the party set out from the port of Falmouth near Cornwall at 14.00 on the 26th of March 1942.

They were sailing into a situation where they would be up against enormously bad odds. There were approximately 5,000 German troops stationed in the St Nazaire region in the spring of 1942. Moreover, the port and dry-dock itself were defended by the 280th Naval Artillery Battalion, with 43 large anti-aircraft guns that could also be used against oncoming ships in the Bay of Biscay. Moreover there were several German surface ships docked there, as well as two U-boat submarine flotillas.

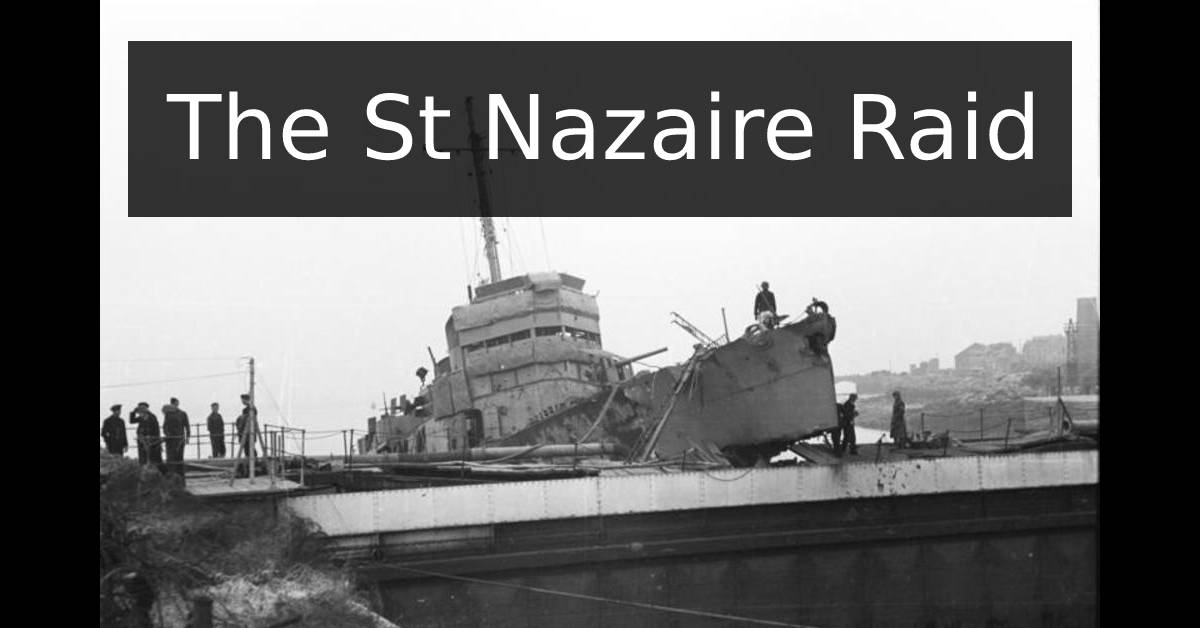

The flotilla began its journey into St Nazaire out of the bay at 22.00 on the night of the 27th. A German naval ensign was raised to try to deceive any German lookouts into thinking it was a friendly convoy, while British RAF planes began a bombing raid on the port to try to create a diversion. Shortly after midnight Ryder’s small fleet neared the port. However, at 1.22am, while still about a mile from the gates of the dry-dock, German floodlights locked onto the convoy. Within minutes they were under attack. In a flurry the small British flotilla now made for the dock. The Campbeltown made it through, though many of the smaller vessels did not and even those which did were generally sinking or on fire within minutes. At exactly 1.34am the HMS Campbeltown reached its goal when it crashed into the gates of the dry-dock. Such was the impact that it was driven 33 feet up onto the gate, making it impossible to quickly dislodge it.

What followed was hours of chaotic fighting. Most of the other ships were crippled. Eventually only four of the smaller motor launches would make it back to England. Many of the crew and commandos had bailed out and were now engaged in bitter fighting in the streets of St Nazaire and the surrounding region as dawn began to break in western France. Eventually, of the 612 men which left Cornwall on the 26th, 169 were killed during the combat, 228 made it back to Britain and 215 were captured by the Nazis. Five even made it south over the Pyrenees in the days and weeks that followed and eventually to British territory in Gibraltar.

But the mission was a resounding success. The explosives hidden in concrete on board the Campbeltown were timed to detonate. They did so at noon on the morning of the 28th of March. In the process several hundred German troops were killed and the dry-dock at St Nazaire was effectively destroyed, making it non-operational for the remainder of the war. So destructive was the explosion that it was 1948 before the dock was returned to use.

St Nazaire has been recognized as one of the most daring raids in military history. In total 89 members of those involved received the Victoria Cross, the most prestigious British military award, granted for ‘valour in the presence of the enemy’. Furthermore, it achieved its overall strategic goal. Without the option of being able to dock at St Nazaire, the Tirpitz was never sent into the Battle of the Atlantic and it was eventually destroyed by an RAF attack while it was stationed in the fjords of Norway late in 1944. Thus, St Nazaire was not just a daring British operation, but a highly significant strategic victory in the wider Battle of the Atlantic.