There are few wars that have ended as strangely as the Second World War in the Pacific Theatre. For instance, the Russian Federation and Japan are theoretically still at war with each other, as certain territorial disputes concerning lands along the north-west of the Pacific Ocean were never fully resolved in 1945. More curious still was the fact that many Japanese garrisons and brigades refused to accept that the Empire of Japan had been defeated in the autumn of 1945 and the emperor in Tokyo had signed the official declaration of surrender on the 2nd of September 1945. Some of these soldiers were confined to small bunkers and military strongpoints on isolated islands around the Japanese archipelago or various other islands in the western Pacific. Accordingly some simply did not know for an extremely long time that the war was over and in some instances continued to fight against anyone who approached their positions for months or even years after the war ended. Some of these so-called Japanese holdouts fought on until the late 1940s or even much later, cut off from the world and still determined to fight a war which was over.

Of all of these Japanese holdouts a handful stand out. Teruo Nakamura was the most resilient. An Amis aborigine from Taiwan, Nakamura had been stationed on the island of Morotai in the north of what were the Dutch East Indies at the start of the Second World War, but which subsequently became part of Indonesia. The Allies overran Morotai in September 1944, but Nakamura and several others remained in the woods and refused to surrender. When the war ended a year later they received no word of this and continued to fight on as guerrilla soldiers in the jungle. Eventually, in 1956 Nakamura’s companions gave up the cause and returned to civilization, but Teruo continued his fight alone and continued to reside in a small hut which he constructed on a 20 by 30 meter field in the middle of the Morotai wilds for the next twenty years. It was not until 1974, when the Indonesian government decided to intervene, that Nakamura was brought back to civilization as it were. He was the last Japanese holdout to accept that Japan had lost the war, over 28 years after the war ended.

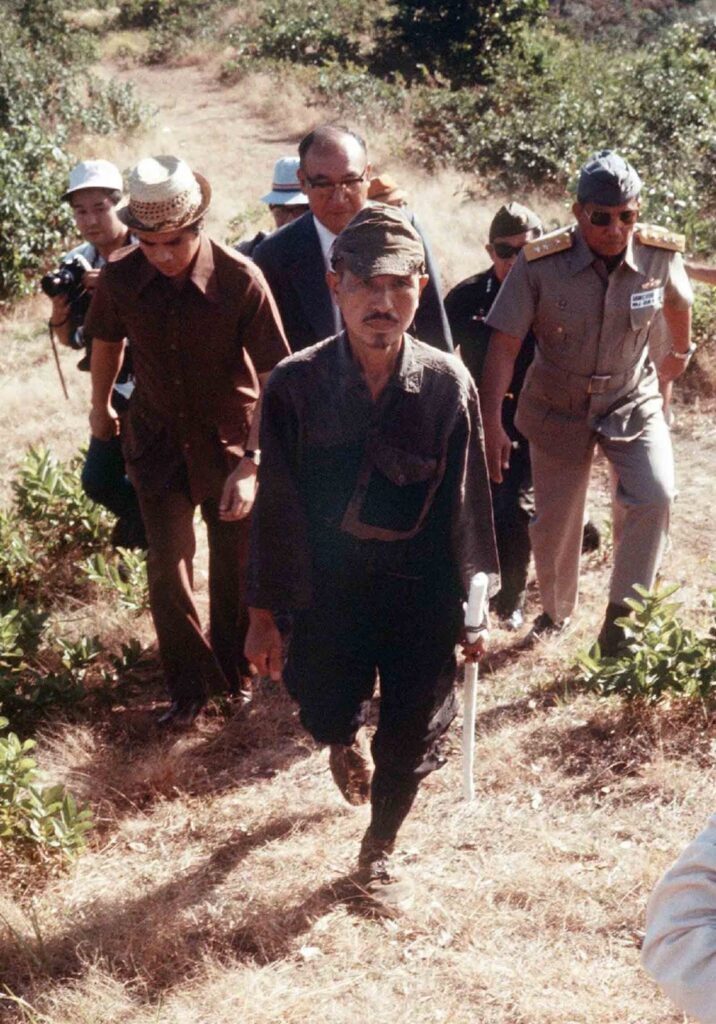

Nakamura’s story is eclipsed by just one other, that of Hiroo Onoda. Onoda was the penultimate Japanese holdout to surrender and only eventually ended his own personal war a few weeks before Nakamura did in 1974. Onoda was a Japanese native from Wakayama prefecture who was born in 1922. During the early years of the war he trained as an intelligence officer and was committed to the ultra-nationalist and quasi-fascist political ideology of the Empire of Japan. On the 26th of December 1944 he was sent to Lubang Island, one of the north-westernmost islands of the Visayas, the Middle Philippines or islands which dot the archipelago between Luzon in the north and Mindanao in the south. Here he was commanded to do everything in his power to stop the Allied re-conquest of the Philippines by destroying the airstrip which was being developed by the Americans there and attacking various other sites as the island was still an active theatre of the war.

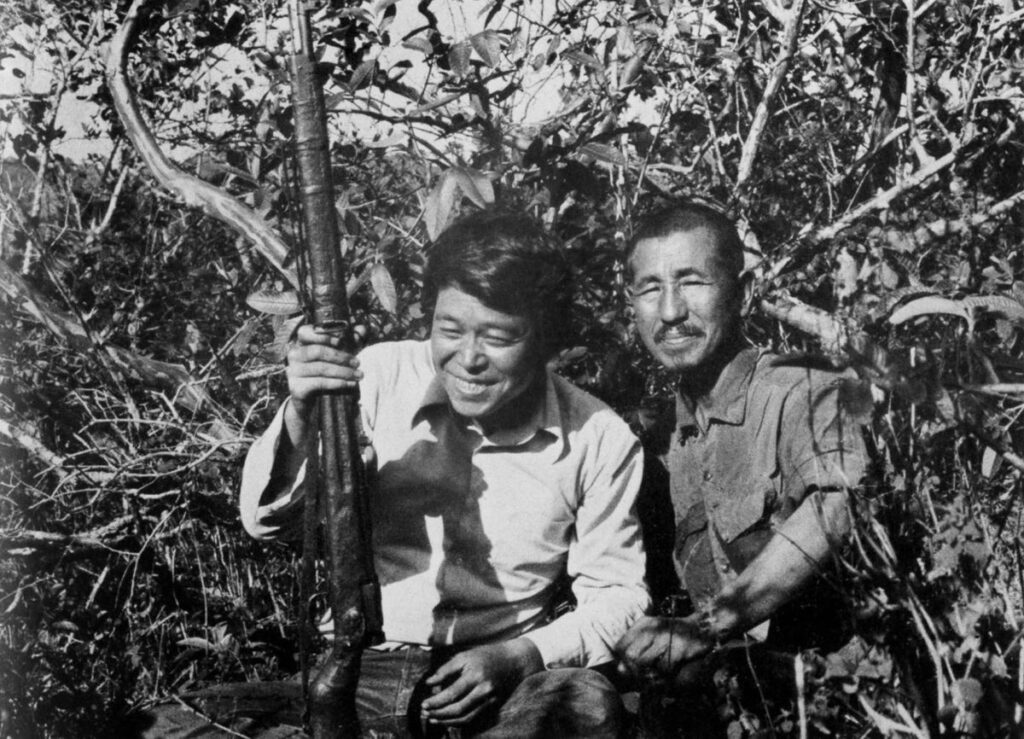

Image: Norio Suzuki via reddit

Onoda and his fellow soldiers were presented with their first opportunity to surrender in February 1945 when the US and their allies took full control over Lubang Island. However, Onoda decided to continue the fight against the Americans and their allies and commenced a campaign of guerrilla attacks on Allied personnel and bases. This continued for months thereafter, even as the war was heading towards an inexorable conclusion in the wider Pacific Theatre. Once atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and then needlessly on Nagasaki the emperor in Tokyo announced Japan’s intention to surrender. But it was not until October 1945 that Onoda and his small group of fellow soldiers first came across a leaflet with a command from General Tomoyuki Yamashita, which had been dropped on Lubang Island, like many other islands across the Western Pacific, alerting them that the war was over and they should now surrender. Onoda, like many other Japanese holdouts, believed this was a ploy by the Americans and so he refused to countenance surrendering.

As the months and then the years passed Onoda, like Nakamura on Morotai island to the south-west, was gradually abandoned by his fellow holdouts, many of whom simply walked out of their camp and surrendered to the Filipino authorities. However, a small coterie of soldiers continued to fight with him. They engaged in attacks on military and civilian targets, often ending up in shootouts with local fishermen whom they allegedly believed to be Allied soldiers. Despite repeated leaflet drops, which in the 1950s included signed letters from their own family members, they continued to defy the request to surrender. But as the years passed, their numbers declined, until in 1972 it was just Nakamura who was left. His last companion, Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka, was killed that October as they were attacking a rice depot as part of their guerrilla activities.

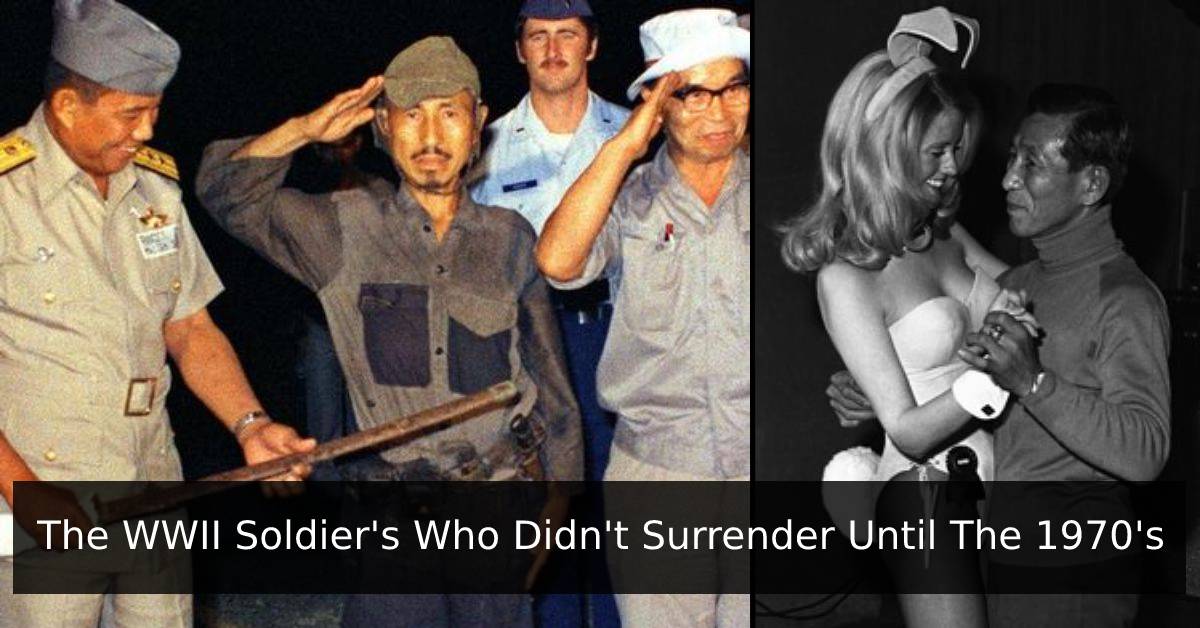

Eventually, on the 9th of March 1974, Onoda was visited in the jungles of Lubang Island by Major Yoshimi Taniguchi. Taniguchi had been Onoda’s commanding officer thirty years earlier when the war was still actually underway. He had been contacted as an individual who was best positioned to implore Onoda to surrender. Thus, when he met with his former commander in the mid-spring of 1974, nearly thirty years after his arrival on the island, Onoda agreed to surrender. He turned over his sword, his rifle, ammunition and grenades, as well as a dagger which his mother had given him in 1944 to kill himself with if the other option had been to face dishonor by surrendering. Now that he finally knew the war was over he no longer needed it.

There is a romanticized element to Onoda’s story, one which he created himself to a large extent. In late 1974, just months after his return to civilization, he published an autobiography entitled No Surrender: My Thirty-Year War, or 30 Years War on the Island of Lubang in Japanese. This detailed his wartime service and the quarter of a century of additional resistance thereafter. In this he depicted he and his fellow soldiers’ efforts as being those of a brigade of Japanese troops bound by ideas of honour and a refusal to surrender. But this is not the case. For instance, Onoda depicts himself and his fellows as targeting military sites exclusively, but the reality is that they also engaged in attacks on civilian targets and Onoda is believed to have killed approximately 30 civilians during his time in the Philippines. As such, while many people have romanticized the idea of the Japanese holdouts that refused to surrender, the reality was that these were soldiers who were ideologically committed to a brutal form of Far Eastern ultra-nationalism. When they were finally brought to surrender and the Empire of Japan began to transform itself in an astonishing way, which was mirrored in West Germany after 1945, the world was much the better for it.